calsfoundation@cals.org

Norfork Dam and Lake

Built on the North Fork River, just upstream from its confluence with the White River in Baxter County in north-central Arkansas, Norfork Dam and Lake are named after the nearby town of Norfork (Baxter County). The dam was authorized by Congress in the Flood Control Act of 1938, and construction began in the spring of 1941, making it one of the oldest U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ multi-purpose concrete structures. The reservoir extends north from the dam site to near Tecumseh, Missouri, and covers portions of Baxter and Fulton counties in Arkansas and Ozark County in Missouri. The drainage area controlled by the reservoir is about 1,806 square miles. The project also contains a powerhouse that houses the generators and turbines for generating hydroelectricity.

The North Fork River was a strong candidate for a tributary flood control project. The Corps noted it was a primary contributor to flooding in the White River because of its steep banks and big feeder streams, which frequently swelled quickly during periods of runoff. For a number of years, the Corps and private entities had studied the site for potential hydropower use, as well. Norfork Dam was one of the six original dams and reservoirs authorized for the White River and its tributaries in the comprehensive Flood Control Act signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on June 28, 1938. Congressman Claude Albert Fuller sponsored this flood control legislation, and U.S. Senator John E. Miller helped to pass the 1938 act, opening the way for the construction of Norfork Dam. Securing funding for Depression-era projects at the time of a possible impending war, however, was difficult. Congressman Clyde T. Ellis argued that a dam with a power plant was immediately needed for any increased manufacturing requirements during possible wartime production demands. He succeeded in obtaining funding and additional authorization for hydropower in the Flood Control Act of 1941, and the Little Rock District of the Corps of Engineers awarded the construction contract to the Utah Construction Company and Morrison-Knudsen Company, Inc.

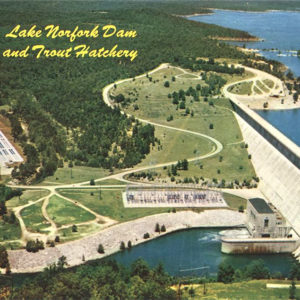

The length of the dam is 2,624 feet. The spillway gross crest length is 568 feet, and there are twelve spillway gates. Elevation to the top of the dam is 590 feet. At a normal lake level of 552 feet mean sea level (msl), the lake covers 22,000 acres and has a shoreline of 380 miles. The lake’s level at the top of the flood pool is 580 feet msl, covers 30,700 acres with a shoreline of 510 miles, and contains 732,000 acre-feet of water.

Initial plans for the dam called for two generators, although the project included four eighteen-foot-diameter penstock tubes (conduits that carry water to the turbines), which would allow the installation of up to four generators at a later date. The World War II–era War Production Board cut this to one generator in the summer of 1942. The dam and powerhouse were operational by 1944, though a second generator was installed and in use by February 1950. Two extra penstocks remain plugged with concrete. The current power plant utilizes two 40,000-kilowatt generators.

A sufficient supply of aggregate from nearby areas and possible quarry locations helped determine that the dam would be entirely of concrete. Approximately 1.5 million cubic yards of concrete were required, and the dam was said to be the fifth-largest concrete dam in the country at the time.

The Corps chose the dam’s final location, from four possible sites, 4.8 miles upstream from the town of Norfork at the confluence of the White and North Fork rivers. A spur railroad line off the Missouri Pacific was built from Norfork to the dam location to move equipment, materials (including some 1.2 million barrels of Portland cement), and nearly 2,000 tons of reinforcing steel—not to mention gates and miscellaneous metal. During construction, a total of 27,000 railroad cars were moved along the spur.

Because of wartime shortages, spillway gates were installed sometime later. In the meantime, concrete bulkheads were used to raise the lake level above the bottom of the spillway openings to 656 feet above mean sea level. Rains caused the lake level to exceed the temporary bulkhead elevation by five feet at least twice in April 1945. When completed, Norfork Dam reduced eighteen of the highest flood crests (from February 1945 to April 1947) on the White River at Calico Rock (Izard County) by an average of 3.31 feet. Accumulated flood losses prevented through fiscal year 2009 are estimated at $68.4 million.

During 1940, several hundred small farms were abandoned in Baxter County and left in foreclosure. However, the construction of a dam in the area meant prospects for work during the Depression. As soon as word of the approval of Norfork Dam appeared in the newspapers, locals began contacting Ellis to inquire about jobs. Over the four-year course of the project, the average number of workers employed on both the dam and powerhouse was 815.

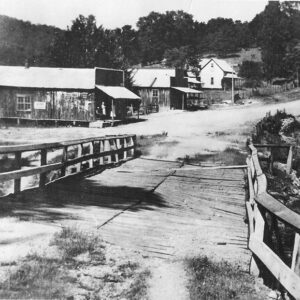

Farmland around two communities along the river—Henderson (Baxter County) and Bakersfield, Missouri—were inundated. Around Henderson, about 400 landowners had to relocate. Some twenty-six cemeteries were moved. Crops continued to be harvested into the late fall of 1942. The lake began to fill by February 1, 1943.

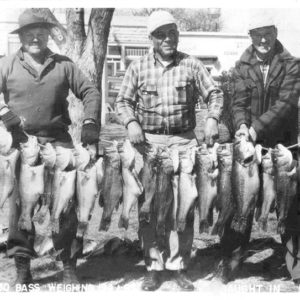

Fishing is a large recreational component of the lake and tailwater. The Arkansas Game and Fish Commission (AGFC) began introducing striped and hybrid bass into the lake in the late 1970s. Due to the stocking of species such as bass, walleye, crappie, and red-eared sunfish, the lake has become a popular Mid-South fishing destination. A major fish attractor project sponsored by the commission also continues to provide habitat for many of the species.

The Norfork National Fish Hatchery was constructed in 1957 on 43.9 acres below Norfork Dam. Construction and operation of the hatchery comes under the Department of the Interior’s U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The hatchery was authorized on August 4, 1955, as part of a federal mitigation plan, as Corps projects across northern Arkansas and southern Missouri changed parts of the White River below the dams into cold-water environments. Species of trout were put into the tailwaters to replace the loss of smallmouth, walleye, and other cool-water species native to the river. Fish production at the Norfork hatchery began in 1957. Hatchery facilities were doubled in size in 1964. As of 2009, the Norfork hatchery produces more than 500,000 pounds of trout annually, totaling more than 2 million fish for tailwaters in Arkansas and Oklahoma.

The Corps maintains seventeen parks around the lake. The Robinson Point National Recreation Trail, the Norfork section of the Trans-Ozark Trail, and short loop trails in some of parks also provide hiking opportunities.

For additional information:

Clay, Floyd M. A History of the Little Rock District, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 1881–1979. 2nd ed. Little Rock: Little Rock District, Corps of Engineers, Department of the Army, 1979.

Cochran, Michael. “The Norfork Project.” West Plains Gazette 7 (Summer 1980): 25–42.

Norfork Dam. Magazine produced by the Norfork Dam Celebration Committee, May 1941.

Norfork Dam and Reservoir Project Arkansas and Missouri, North Fork River, White River Watershed. Little Rock: Little Rock District, Corps of Engineers, Department of the Army, 1948.

“Norfork Lake.” U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Little Rock District. https://www.swl.usace.army.mil/Missions/Recreation/Lakes/Norfork-Lake/ (accessed March 1, 2022).

Shiras, Frances H. “Norfork Dam.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 4 (1945): 150–158.

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Water Resources Development in Arkansas. Dallas, TX: U.S. Army Engineer Division, Southwestern, 1995.

Scott Branyan

Rogers, Arkansas

Beaver Dam and Lake

Beaver Dam and Lake Bull Shoals Dam and Lake

Bull Shoals Dam and Lake Fly-fishing

Fly-fishing Greers Ferry Dam and Lake

Greers Ferry Dam and Lake Salmonids

Salmonids Before Norfork Lake

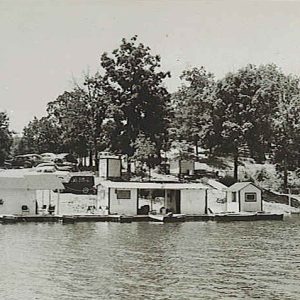

Before Norfork Lake  Cranfield Landing

Cranfield Landing  Fishermen

Fishermen  Henderson before Lake

Henderson before Lake  Henderson Ferry

Henderson Ferry  Norfork Dam

Norfork Dam  Norfork Dam Construction

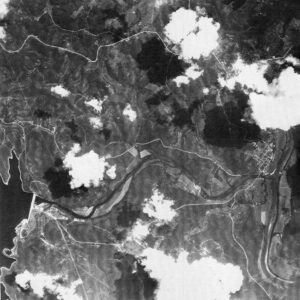

Norfork Dam Construction  Norfork Dam Aerial View

Norfork Dam Aerial View  Norfork Dam

Norfork Dam  Norfork Lake

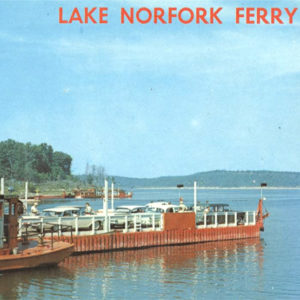

Norfork Lake  Norfork Lake Ferry Crossing

Norfork Lake Ferry Crossing  Norfork Dam and Lake

Norfork Dam and Lake  Norfork Lake Ferry

Norfork Lake Ferry  Norfork Lake Ferry

Norfork Lake Ferry  North Fork River Bridge

North Fork River Bridge  President Truman at Bull Shoals

President Truman at Bull Shoals  Red Bank Landing

Red Bank Landing  Tracy's Landing

Tracy's Landing  President Truman at Cotter

President Truman at Cotter  Worker Village

Worker Village

James Jones wrote portions of From Here to Eternity while staying in a trailer with two of his friends on Lake Norfork in Baxter County. Several years ago, a friend who is a TV writer asked me if I knew about this and also asked if James Jones and I were related. I communicated with a group who were dedicated to the James Jones history, and they confirmed the story about the trailer. I had a personal interest in obtaining this information since as a young man, maybe fifteen, I had witnessed two men in a Jeep pulling an aluminum trailer after crossing Lake Norfork on a ferry. I was envious of their freedom. It dawned on me after learning this story that I was probably seeing James Jones and one of his partners leaving, if my memory is correct, for Kansas. Jones then moved on to California and finished the book.