calsfoundation@cals.org

Pre-European Exploration, Prehistory through 1540

The pre-European history of Arkansas begins 13,500 years ago in the Pleistocene epoch, when cold weather prevailed over most of North America. Our understanding of life in Arkansas since then will never be complete because many archaeological sites have been lost through erosion, human development, and vandalism, and most ancient fragile and perishable objects have decomposed over the centuries. It is possible, however, to describe the general characteristics of life in Arkansas over the last 12,000 years based on discoveries made here, similar finds made elsewhere in North America, and lifestyles of modern nonindustrial hunters who lived in remote areas of the earth in recent times. Archeologists divide this time into five periods, each having distinctive lifestyles, cultural practices, and artifacts that are found across most of eastern North America.

Paleoindian Period

People were in Arkansas during the Pleistocene epoch, but their arrival date and lifestyles are largely unknown. The oldest known artifacts are chipped stone Clovis dart or spear points, named for the discovery site in New Mexico, that are approximately 13,500 years old. Clovis point makers are called Paleoindians. These artifacts have been found in agricultural fields, in construction sites, and on gravel bars in large river valleys. No intact Clovis settlements are known yet in Arkansas, although many sites exist elsewhere. One question that archaeologists debate today is whether Clovis represents the first wave of humans into the New World or whether there were other migrations hundreds or thousands of years earlier. There have been no discoveries in Arkansas indicating that people were here before the Paleoindians.

Clovis sites show a hunting-and-foraging lifestyle. The cooler climate created a mixture of cool-loving and warmth-tolerant vegetation species unlike any vegetation communities seen today. Animal populations were also a mixture of modern species, such as deer, rabbits, and turtles, and large herbivores, such as mastodons, giant ground sloths, and Pleistocene bison that became extinct at about this time, as did some predators, such as cave bears.

Pleistocene animal bones are found in the Arkansas Delta, in Ozark caves, and in river valleys. So far the bones are from animals that died naturally. Elsewhere, Paleoindians killed Pleistocene animals, so future discoveries of butchered animal carcasses will probably be made.

Sites studied elsewhere offer evidence of Paleoindian lifestyles. Hunting tools included throwing sticks, snares, and nets. For some prey, hunters used spears propelled by a spear thrower known as an atlatl. The cooler environment made some food like nuts scarce, but both plants and animals were used for food, clothing, and other necessities. Paleoindians did not have any domesticated plants or animals, except perhaps the dog.

People lived in small groups and followed the natural cycles of abundance in plant and animal populations. Studies of modern hunters like the Inuit, the South African San, and the Australian Aborigines show that groups were likely made up of families linked by marriage and friendship. A high value was placed on harmonious interpersonal relationships and on sharing work and supplies. The average life expectancy was probably between twenty-five and thirty-five years. There were no permanent dwellings, but temporary shelters and storage facilities were constructed for comfort and safety.

Archaeologists disagree about whether Paleoindians traveled long distances or remained in familiar territories without setting up permanent homes. Whichever is true, Arkansas was very thinly populated.

Dalton Period

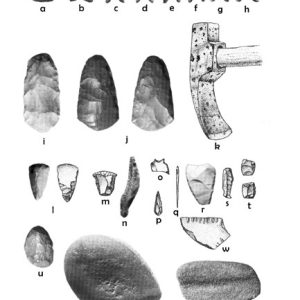

Between about 11,000 and 13,000 years ago, the Arkansas climate moderated. Some animals became extinct, stream flow changed, and deciduous forests expanded. Human societies also changed as people developed new technologies and subsistence patterns. Dalton sites are marked by distinctively shaped spear points that are found across much of eastern North America. The point distribution shows that there was a widespread Dalton lifeway oriented toward streams and deciduous forests. Another distinctive artifact is a chipped stone adze, a tool probably used for woodworking tasks.

Dalton points are found at hundreds of sites in Arkansas. Dalton people occupied all parts of Arkansas, including Ozark bluff shelters and river-side camps. A few of these sites have been excavated, and they offer some information about Dalton lifeways.

In the lowlands west of Crowley’s Ridge in northeastern Arkansas, the Brand and Lace sites were Dalton campsites. Because the sites lacked sturdy dwellings and neither plant nor animal remains were preserved, there is no direct information of subsistence activities present. Many different kinds of stone tools were recovered, including chipped-stone spear points, cutting, scraping, and piercing implements made from flakes, and bifacially shaped blanks that are templates for the later manufacture of a variety of tools. These indicate that butchering meat, scraping bones, and making and repairing tools took place at these two sites. The spears were used with atlatls or as stabbing spears. The bow and arrow had not yet appeared in the New World.

These sites and others indicate that Dalton people were hunters and gatherers using a variety of wild animal and plant foods over the course of each year. Timber and nuts were important as raw materials and food, but it is unlikely that the landscape was completely “modern” with regard to the abundance and distribution of plants and animals that became favored foods in later times.

Like Paleoindians, Dalton groups probably consisted of families related by kinship and mutual dependence. Some archaeologists believe that these people were “settling down” to reside within a familiar foraging territory rather than moving from one new location to another throughout their lives. One theory proposes that a group lived in a series of base camps during a year, with work parties leaving the base to gather food, tool-making stone, or other necessary resources. An alternative theory is that the entire group moved from location to location to take advantage of the seasonal abundance of valuable resources. Too few Dalton sites have been studied in Arkansas to verify either theory.

One site in northeastern Arkansas produced a rare glimpse of Dalton ritual activities. The Sloan Site yielded several caches of finely chipped stone artifacts rarely found in typical Dalton sites. These included spear points, adzes, and a variety of other piercing, cutting, and pounding tools. Most showed no signs of being used. Tiny pieces of bone were identified as human. The arrangement and fine condition of these artifacts indicate that the site was a cemetery where members of a local Dalton group were buried with gifts or offerings. If this is true, the Sloan Site is the oldest identified cemetery in North America.

Archaic Period

By 6,000 BC, a new lifeway based on hunting and gathering but emphasizing new technologies and settlement patterns was in place across North America. This lifeway persisted in Arkansas until about 500 BC and was a successful adaptation to the diverse resources available in forests and streams in the state.

The environment changed gradually during this time. A long period of increasingly dry and warm climate conditions called the Hypsithermal began between 5,000 and 8,000 years ago. In many locations in Arkansas, grasslands expanded, deciduous forests shrank in area, and the distribution of resources attractive to humans was different from both the preceding and the subsequent millennia. About 5,000 years ago, the Late Archaic began with a gradual return to cooler and moister conditions similar to those in Arkansas in modern times.

During this period, people still depended on wild resources, and groups moved from one location to another when resources became scarce or abundant. Archaic people favored locations in forests and near streams, but their camps and work sites are found throughout Arkansas in settings like Ozark rock shelters, high promontories overlooking valleys, and alluvial lowlands. Thousands of Archaic sites have been discovered, but few have been studied. Therefore, there is only a general picture of this way of life.

Archaic technology was similar to the preceding Dalton, with chipped stone tools used for many purposes. Spears were tipped with stone projectile points, and some weapons were propelled by atlatls. Bows and arrows were not known. Chipped stone was used for cutting, scraping, chopping, and piercing for gathering food, making clothing, and numerous other tasks. During the Archaic, people discovered and began to mine the bedrock deposits of Ouachita Mountain novaculite, Ozark Mountain cherts, and other non-local stones and minerals. Stone tools were also made by grinding as well as chipping. Axes and other woodworking tools are the most notable and were used for chopping wood, making other tools, and probably for fashioning dugout canoes for river travel. Archaic tool kits included needles and weaving tools, nets, baskets, snares, and bags.

Archaic people are believed to have lived in small social groups that moved periodically within a home territory. Some sites were revisited for generations, resulting in dense accumulations of broken stone tools and manufacturing debris, cooked animal bones, fire-blackened soil, and other garbage. No permanent dwellings have been found, but humans and pet dogs were buried at some camps.

Although people were still thinly scattered, populations grew during the Archaic. Social groups exchanged durable goods and possibly food, spouses, and information with neighbors. In the late Archaic, rocks and minerals from Arkansas were distributed as far as modern-day Louisiana and Mississippi, where they were used for tools, jewelry, and other items. These included novaculite, slate, hematite, lamprophyre, and quartz crystals.

In addition to goods, a variety of technological innovations seem to have spread from group to group during the Archaic. One innovation was gardening. Corn and beans were not the first domesticated plants in North America. Gourds and squashes came first, used for containers and sources of nourishing seeds. Native annuals, plants identified as weeds today, rich in oily and starchy seeds, became a significant item in human diets. By the Late Archaic, about 3,000 years ago, several domesticated plants, including chenopod, sumpweed, and sunflower, along with squashes and gourds, were grown in Arkansas. Ozark rock shelters have yielded domesticated and wild plant seeds stored along with fruits, nuts, and other supplies like baskets and tools.

These first gardeners used domesticated plants to supplement a diet still based on wild foods. This method of gardening did not require people to live in permanent communities or create large agricultural fields. Many questions about this “food revolution” remain. It is not known whether all native people in Arkansas were using domesticated plants. Archaeologists disagree about whether gardening first took place in the moist alluvial valleys with easily tilled soils or in the less lush uplands where wild plants were harder to find. It is also unknown whether native gardeners developed their skills and crops independent of outsiders or whether the cultivated plants and gardening skills were introduced into Arkansas from people of neighboring regions.

Mound building is another innovation that appeared during the Archaic. About 5,000 years ago, some people in the uplands west of the Mississippi River began constructing mounds that are thought to be centers for periodic political and ritual activity for a dispersed foraging population. Political leadership was probably limited, informal, and invested in individuals with personal charisma and large family support groups. Nevertheless, mound building and the development of central political or ritual places demonstrate that scattered populations were willing to undertake collective activities for special purposes. Mounds and cemeteries also are material representations of a group’s claim over a particular landscape within which families moved from place to place.

Archaic mound building reached its greatest expression in northeastern Louisiana about 3,500 years ago where the Poverty Point Site, an elaborate 400-acre arrangement of mounds and other earthworks, was the center for a large and highly influential Late Archaic society. Poverty Point extended its influence far into Arkansas to acquire goods such as hematite, magnetite, quartz crystals, slate, and novaculite from the Ouachita Mountains. At Poverty Point, these were made into tools, jewelry, and other objects that were also redistributed over a wide area of the lower Mississippi Valley. Poverty Point people may have traveled into Arkansas for these resources or acquired them through trade with groups residing in the area. No Archaic mounds of comparable scale have been recorded in Arkansas.

Woodland Period

About 2,500 years ago, pottery first appeared in Arkansas, marking the beginning of the Woodland Period. Pottery containers represent new dietary practices that probably included the use of seeds, nuts, and other plants that were boiled into stews, soup, and mush. Potters express cultural and aesthetic values through vessel shape and decoration, making even broken pottery sherds rich sources of information for archaeologists. They employed specific recipes for clay and temper—that is, granular or fibrous material added to raw clay to allow pots to withstand temperature and moisture changes during manufacture and use—in making their pots. Local customs also dictated how pots were shaped and decorated. Archaeologists use this information to identify local and short-lived customs within communities and to study the relationships between neighboring communities through time. Woodland pottery differs from one part of Arkansas to another and illustrates some fundamental cultural differences between people living in different parts of the state. These differences become more distinct in the 1,000 years before Europeans arrived.

Because pottery was not highly portable, people gave up some mobility for convenience in preparing food that was new or improved through cooking, given that cooked foods provided quick carbohydrate and fat calories and were easier for children and older people to digest. Woodland people lived in all parts of Arkansas in locations ranging from upland rock shelters to alluvial river valleys in camps, residential sites, and religious or political centers. Woodland diets were still dominated by wild plant and animal resources. In the Ozark highlands, some groups grew squash, gourds, and native seed-bearing plants, but it is not known whether people elsewhere in the state practiced gardening through most of this period. Animals were hunted with spears, probably with nets and traps of various sorts, and possibly with bolas—stones tied together by short lengths of cord and thrown at prey to entangle it and bring it down. Bows and arrows appeared about 1,400 years ago in the Late Woodland. Chipped stone axes or adzes and ground-stone plummets and boatstones were also made. Plummets are prehistoric equivalents to plumb bobs, drop-shaped ground stone objects with a narrow end pierced or encircled by a groove where a cord can be tied. They may have served as weights or as charm stones. Archaic people first made plummets, but they are still found in the Woodland period. Boatstones, as their name indicates, are shaped like small ground stone canoes and are believed to be counterweights for atlatls or throwing sticks.

Woodland gardeners were the first people in Arkansas to raise corn (maize), first in very small amounts in the Ozark highlands and the central Arkansas River Valley between 1,200 and 1,400 years ago. Domesticated elsewhere, maize may have been introduced to groups in Arkansas from the Southwest. These would have been little more than ritual or novelty plants; there is no indication that maize became a significant food until less than 1,000 years ago.

Woodland people do not seem to have lived in permanent villages. Sturdy dwellings have been found where one or a few families may have resided, but campsites that were occupied occasionally over the course of years or generations are far more common. These camps have middens, or garbage deposits where stone tools, pottery, burnt rocks from campfires, discarded animal bones, mussel shells, and other waste material, as well as human and dog burials, have been found.

During this time, cultural traditions in different corners of Arkansas each became distinct. In southwestern Arkansas, the Fourche Maline culture is characterized by dark middens containing an abundance of plain pottery, projectile points and other stone tools, animal bones, and broken burned rocks. Woodland sites in east Arkansas often have plain, cord-impressed, or red-filmed pottery in middens, evidence of dwelling structures, and large underground pits used first for storing food and later as garbage containers. People in what is now northern Arkansas shared some cultural practices, like making pottery vessels with pointed bottoms and cord-roughened surfaces, with societies further north in the Midwest. These regional differences and others probably indicate populations were forming large cultural groups akin to historically known tribal societies.

Mound building became more common and complex among Woodland peoples. Some mounds were burial monuments and crypts, some were platforms for special buildings, and others were erected to mark the location of public ritual and social spaces. Not all Woodland people in Arkansas built mounds, however.

The greatest mound center in Arkansas is the Toltec Site, center of the Plum Bayou culture, situated in Lonoke County in central Arkansas near Little Rock (Pulaski County) and used between 900 and 1,400 years ago. Plum Bayou culture dominated central Arkansas for centuries and affected the development of complex societies in the Arkansas River Valley near Fort Smith (Sebastian County) and along the Red River in southwestern Arkansas. Plum Bayou people sought rock and mineral resources from the Ouachita Mountains that they made into tools and decorative objects.

Mississippian Period

Between 1,000 and 1,200 years ago, profound changes took place among many native societies across eastern North America. The descendants of these people were also the first to encounter European explorers and colonists in the sixteenth century.

Mississippians were true farmers. They raised maize, squashes and gourds, tobacco, sunflowers, beans, and additional ritual and medicinal plants in fields near permanent homesteads and villages. Although they still collected wild food, these people subsisted largely on garden crops. In good years, this meant surplus foods for farmers as well as political leaders and other specialists, such as priests and artists. In bad years, food shortages brought starvation and pressure for warfare over land, food, and the labor of client communities. This commitment to a farming way of life meant fundamental changes in social organization, technology, religious beliefs, and practices during the Mississippian Period.

Mississippian sites are different from Woodland predecessors. The largest and most complex sites were political and religious centers, with one or more flat-topped mounds that were platforms for public events and residences of political and religious leaders. Public works such as ditches and earthen embankments may be present, and some sites may have had encircling defensive wooden palisades. Some sites, like Parkin Site in Parkin (Cross County), had a large population crowded into the community. Others were scattered small farmsteads and hamlets, and only a few people resided regularly at the mound center.

Mississippian society was hierarchical; some individuals and families were more influential, wealthy, and privileged than others, and these differences were evident in life and death. Privileges may have been inherited or earned through charisma, valor in warfare, wealth, and other personal qualities. Political leaders, and perhaps also religious leaders, had the power to commandeer the goods and labor of others to construct public works, wage war, carry out community-wide celebrations and events, and support the efforts of nonfarming specialists, such as potters.

Some people in Mississippian society possessed objects that were denied to everyday citizens. These included costumes and ritual paraphernalia. These special objects were transported long distances and possessed by leaders of equivalent power, including some important leaders in Arkansas. These objects and the symbolism they embodied have been identified with the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex. The religious beliefs, mythology, and rituals connected to these objects were shared among Mississippian people across much of the Southeast during this time. Scholars disagree on the question of who possessed ritual knowledge: some believe only elite members of society possessed it, while others believe all members of society shared the same understanding. Some artwork painted and pecked in rock shelters were made at this time and may be from ritual activities such as spirit quests carried out by individuals from villages in the lowlands.

Mississippian tools and weapons included bows and arrows, and perhaps blowguns, and large chipped stone hoes used to break up alluvial soils in agricultural fields. People with special skills made the costumes and paraphernalia used in rituals and public displays, elaborate non-utilitarian artifacts of shell, pottery, and other media. For instance, pottery was no longer limited to cooking, storing, and serving functions but included effigy figures of human, animal, and supernatural creatures used for special events.

Prehistoric Caddo

In southwestern Arkansas and neighboring areas of present-day Louisiana, Texas, and Oklahoma, a regional version of Mississippian society arose about 1,000 years ago and is believed to be ancestral to historic Caddo culture. Like the Mississippian, prehistoric Caddo economy was based on farming and collecting wild resources. Caddoan settlements were mainly small, semi-isolated farmsteads with one or more dwellings, storage and work facilities, and family graveyards. Family groups residing within a segment of river valley shared traditions in architectural styles, artifacts, and presumably other cultural values. Mound centers with at least one flat-topped mound and one or more additional conical mounds were the political and religious centers for far-flung Caddo communities. Leadership among the prehistoric Caddo was hierarchical and marked by the possession of special exotic and ritually significant objects, such as smoking pipes and costumes, and by special treatment after death.

Prehistoric Caddo were expert potters, like the Mississippians, but shapes and decoration were different. Instead of making effigy figures, Caddo potters covered their simple jars, bowls, and other containers with complex geometric patterns. Caddo also wove baskets, mats, and other furnishings out of reeds, grasses, and split cane. Abundant brine seeps in southwest Arkansas became important salt-making centers for the Caddo; they were still trading salt to neighboring tribes when the French arrived in 1700.

People built mounds throughout Arkansas in the Mississippian Period, even in the Ozarks, but archaeologists cannot yet specify how these people were related to other Mississippian or Caddoan peoples. By the end of the prehistoric period, however, all native Arkansans farmed, lived settled lives in homesteads or villages, had complex social relationships and religious beliefs, and had contact with people outside the region.

These long-distance contacts may have brought the first of many dramatic changes to local residents early in the 1500s. When Spanish explorers engaged the Aztec Empire in the first of many wars of control and conquest in the Americas, smallpox, influenza, measles, and other diseases familiar today began spreading through native cultures. Because these diseases were new to native populations, they spread rapidly, infecting and killing entire communities at a time. No one knows how many people died from these diseases, but conservative estimates are in the millions. Diseases spread from community to community in advance of the Europeans themselves, and it is possible that diseases brought ashore in Mexico reached native people living in and around Arkansas a full generation before Hernando de Soto and his Spanish expedition crossed the Mississippi River into Arkansas in 1541. Although direct evidence of disease has not been found, changes are apparent in settlement patterns and cultural practices around 1500, especially in the Caddo area. The first native Arkansas people described by members of the de Soto expedition may therefore have already been affected by European invasion of the Americas.

For additional information:

Early, Ann M. Caddoan Saltmakers in the Ouachita Valley: The Hardman Site. Research Series 43. Fayetteville: Arkansas Archeological Survey, 1993

———. “Prehistory of the Western Interior after 500 B.C.” In Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 14, Southeast, edited by William C. Sturtevant and Raymond D. Fogelson. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2004

Fritz, Gayle J. “A Three Thousand Year Old Cache of Crop Seeds From Marble Bluff, Arkansas.” In People, Plants, and Landscapes: Studies in Paleoethnobotany, edited by Kristen J. Gremillion. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1997

Goodyear, Albert C. The Brand Site: A Techno-Functional Study of a Dalton Site in Northeast Arkansas. Research Series 7. Fayetteville: Arkansas Archeological Survey, 1995

Jeter, Marvin D., Jerome C. Rose, G. Ishmael Williams Jr., and Anna M. Harmon. Archeology and Bioarcheology of the Lower Mississippi Valley and Trans-Mississippi South in Arkansas and Louisiana. Research Series 37. Fayetteville: Arkansas Archeological Survey, 1989.

Mainfort Jr., Robert C. “The Late Prehistoric and Protohistoric Periods in the Central Mississippi Valley.” In Societies in Eclipse, edited by David S. Brose. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2001.

Milner, George R. The Moundbuilders: Ancient Peoples of Eastern North America. London: Thames and Hudson, 2004.

Morse, Dan F., ed. Sloan: A Paleoindian Dalton Cemetery in Arkansas. Washington DC: Smithsonian Press, 1997

Morse, Dan F., and Phyllis A Morse, eds. Archaeology of the Central Mississippi Valley. New York: Academic Press, 1983

Perttula, Timothy K., Ann M. Early, Lois E. Albert, and Jeffrey Girard. Caddoan Bibliography. Technical Paper 10. 2d ed. Fayetteville: Arkansas Archeological Survey, 2006.

Rolingson, Martha A. “Plum Bayou Culture of the Arkansas–White River Basin.” In The Woodland Southeast, edited by David G. Anderson and Robert C. Mainfort Jr. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2002

Rolingson, Martha A., and Robert C. Mainfort Jr. “Woodland Period Archaeology of the Central Mississippi Valley.” In The Woodland Southeast, edited by David G. Anderson and Robert C. Mainfort Jr. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2002.

Rolingson, Martha R. “Prehistory of the Central Mississippi Valley and Ozarks after 500 B.C.” In Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 14, Southeast, edited by William C. Sturtevant and Raymond D. Fogelson. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2004.

———. Toltec Mounds and Plum Bayou Culture: Mound D. Excavations. Research Series 54. Fayetteville: Arkansas Archaeological Survey, 1998.

Sabo III, George, et al. Human Adaptation in the Ozark and Ouachita Mountains. Research Series 31. Fayetteville: Arkansas Archeological Survey, 1988.

Sabo III, George, and Deborah Sabo. Rock Art in Arkansas. Fayetteville: Arkansas Archeological Survey, 2005.

Schambach, Frank F. “Fourche Maline: A Woodland Period Culture of the Trans-Mississippi South.” In The Woodland Southeast, edited by David G. Anderson and Robert C. Mainfort Jr. Tuscaloosa & London: University of Alabama Press, 2002.

———. Pre-Caddoan Cultures in the Trans-Mississippi South. Research Series 53. Fayetteville: Arkansas Archeological Survey, 1998.

Scholtz, Sandra Clements. Prehistoric Plies: A Structural and Comparative Analysis of Cordage, Netting, Basketry and Fabric from Ozark Bluff Shelters. Research Series 9. Fayetteville: Arkansas Archeological Survey, 1975.

Story, Dee Ann, et al. The Archeology and Bioarcheology of the Gulf Coastal Plain. Research Series 38. Fayetteville: Arkansas Archeological Survey, 1990.

Townsend, Richard F., ed. Hero, Hawk and Open Hand: American Indian Art of the Ancient Midwest and Southeast. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2004.

Young, Gloria A., and Michael P. Hoffman. The Expedition of Hernando de Soto West of the Mississippi, 1541-1543. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1993.

Ann M. Early

Arkansas Archaeological Survey

Dalton Tools

Dalton Tools  Dalton Period Artifacts

Dalton Period Artifacts  Head Pot

Head Pot  Toltec Mounds Site

Toltec Mounds Site

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.