calsfoundation@cals.org

Food and Foodways

Because nutrition is essential to human survival, the production and consumption of food has been central to life in what is now Arkansas for more than ten thousand years. Evolving social customs dictate when, where, and how food is presented. Because of Arkansas’s ties to rest of the South, as well as to the Southwest and Midwest, the core components of local food preparation followed traditional “American” lines, with little impact being felt from the small immigrant population. The globalization of food, mostly via restaurants, came generally after 1960.

Prehistory

The first humans in Arkansas, the Paleoindians, were hunter-gatherers. Despite Arkansas’s lack of excavated and analyzed sites, evidence from adjacent areas suggests that besides hunting the now-extinct mega animals (mammoths, mastodons, large bison, large catfish, etc.), they pursued small mammals as well. They also systematically investigated all the roots, leaves, and berries in order to determine those that were edible or medicinal. Armed with fire, they cooked their food but without the use of pots. Smoking and drying were their principal methods of food preservation.

The successive phases of prehistoric human activity (Archaic, Woodland, and Mississippian periods) witnessed enormous changes in food-related matters. Permanent mobility was replaced first with base camps, then with settled village and farm sites, and culminated in fortified city-states. Over a period of 2,000 years, there emerged a pattern of controlled horticulture that eventually resulted in field-crop agriculture dominated by corn, squashes, and beans. All this variety resulted in more than ninety different recipes for preparing corn. A long list of food-source plants found wanting were discarded along the way. Similar changes overtook preparation. Pottery became increasingly important, both for storing and cooking, and the simple spear point yielded to a wide variety of devices for hunting birds and fish. Indeed, over much of Arkansas, fish became a basic part of the diet. Salt, found naturally in red meats, had to be added to other food items, but Arkansas had a number of salt springs where saline water could be boiled off, leaving the salt.

By the Mississippian Period, class distinctions had emerged, with the elite getting more of the red meat and the masses being fed on corn. Tooth decay—induced by the sugars in the corn—was one drawback associated with the new diet. The Hernando de Soto expedition, which ventured through Arkansas from 1541 to 1543, left the first written accounts of tribal food.

Food ceremonies had evolved as well. Religious rituals blessed the crops and determined when and how food would be consumed. Even the markings and designs on pots showed the integration of foodways into all aspects of culture.

Colonial Era

The colonial era in Arkansas began with the settlement at Arkansas Post (Arkansas County) in 1686. Primarily a trading store, Arkansas Post added an agricultural component during the John Law period (1716–1722) when habitants set up farmsteads on abandoned prehistoric farm land. During the eighteenth century, trade and commerce went up and down the Mississippi River. This traffic continued after 1764, when the French turned their western lands over to the Spanish. Michael Wolf in the 1790s grew wheat, and other European grains were available from the Illinois country. The French and later the Spanish rapidly adapted Quapaw cuisine, especially the consumption of smoked buffalo tongues. Salted tongues were a major Caddo export. The governmental and merchant elite acquired silver and cut glass, indicating that formal dining was not unknown to Frederick Notrebe, François Menard, and Benjamin Fooy and a succession of commandants. Records also show that that the administrative officials consumed considerable amounts of French wines and liquors, with sometimes unfortunate medical results. The local tribe, the Quapaw, integrated with the French hunters, resulting in a hybrid culture that combined European food and alcohol with Indian smoking and drying practices. The Quapaw also quickly adopted European fruit trees, notably peach, which were grown extensively in the Mississippi River Valley.

Nineteenth Century

The passage of Louisiana to American control in 1803 led to major changes. One major source of population came from displaced members of eastern American tribes. A large Cherokee/Shawnee/Delaware contingent settled on Crowley’s Ridge. Besides continuing to exploit the hunting potential of the western region, they also brought cattle and raised corn and other crops. While a Green Corn ritual continued to be practiced, many other elements of traditional religion had been abandoned.

Cattle were another important element, having risen to prominence in the 1790s. The market value lay in the hides, but one result was that settlers perforce consumed much beef. Rendering edible the tough and stringy meat required special cooking skills called barbecuing. The first identifiable specialist in this field was known as Marie Jeanne to the French and Mary John to the Americans. She traveled up and down the Arkansas River, serving as a caterer for large-scale events and using the pit barbeque method (in which the meat was buried among the coals of a fire pit). After gaining her freedom in 1840, she opened her own establishment (tavern/hotel) at Arkansas Post. Presumably it was better than one visited by George William Featherstonhaugh, whose 1844 book, Excursion Through the Slave States, regaled readers with his experiences at a “sort of tavern” kept by “a sort of she Caliban,” whose five forks were named Stump Handle, Crooky Prongs, Horny, Big Pewter, and Little Pickey. Only slowly did the common people adopt forks.

Despite the presence of large herds of cattle, milchers (milk cows) were virtually unknown until the 1850s. American Indians manifested lactose intolerance and hence had little interest in milk or milk products, while the hunters and herders did not take the time needed to maintain a cow.

Early travelers intoned a litany of complaints about both the food and accommodations of early Arkansas. Chickens were not much a part of early cuisine, and William Minor Quesenbury called Northerners “chicken-eaters.” In the agricultural society, as well as in the small towns, the main meal, styled “dinner,” took place at noon. Sundays following church services were noted for “dinner on the grounds,” and it was commonly said that Methodist women would be denied access to heaven unless they brought along a covered dish. (Methodists were a bit economically better off, and hence a covered dish represented a higher order of cooking than that which, for example, prevailed upon the Primitive Baptists.)

The Sunday noon meal—served cold in conservative Protestant families until well into the twentieth century—reflected practices that varied only slightly from country to town. Breakfast came early, often before daylight, and invariably featured hot coffee. “Dinner” was strictly at noon and, in the heat of summer on the farms, was followed by an extended (two-hour) rest; then work began and continued to or even after dark. Supper was often served cold. In towns, businessmen could get up later, and depending on the nature of their work and degree of wealth, they might have dinner as an evening meal, albeit one that was served earlier than was fashionable in cities or in Europe. Later, there evolved a new standard, called “three squares.” These three large meals invariably featured meat. Hard physical labor declined greatly by the late twentieth century, but eating actually increased. Protein overload produced profoundly health-threatening consequences.

The coming of the Americans had added a series of ceremonial eating events. Leading the way was the Fourth of July. Throughout the nineteenth century, this event was celebrated by food and alcohol consumption and included the reading of the Declaration of Independence. Christmas, celebrated by Arkansas’s small Catholic community but rejected by many Protestants, was linked with New Year’s Day; both were festivals of consumption. Eggnog and syllabub, alcoholic drinks, were seasonal to these holidays. Thanksgiving was a Northern holiday that made its appearance in the 1840s, apparently for the first time in Arkansas in Van Buren (Crawford County). Until 1938, its date of celebration depended on a gubernatorial proclamation, and dates varied widely from state to state and from year to year within states.

After Arkansas became a territory in 1819, a more permanent population began to arrive. Food in the log-cabin culture of the antebellum years centered around the fireplace, where food was cooked in cast-iron pots, pans, and spits. Corn and hogs were central—to the point that “meat” for more than 100 years meant pork. Bread was cornbread, as white wheat flour remained inconsistently available. In the absence of grist mills, Yankee iron hand mills superseded the older mortar-and-pestle system. One wedding in Little Rock (Pulaski County) was postponed because there was no white flour with which to make a wedding cake. In a similar circumstance in Van Buren, a cake was prepared, but guests were not to eat it. The cake was cornmeal covered by white icing.

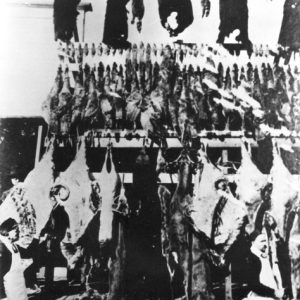

Inside the log cabin, herbs were dried, as were beans and other summer vegetables and such fruits as apples and peaches. Potatoes were stored in a root cellar. All vegetables, including greens, were cooked. After first frost came the annual slaughter of hogs. No part of the animal was wasted, and the products included blood pudding, brains, pickled pigs’ feet, and chittlerlings (“chitlins”) in addition to the hams. What was not eaten fresh was smoked and then stored. Beef, by contrast, was often disposed of by means a shooting contest. The prizes consisted of quarters of beef. Wild game—especially passenger pigeons, doves, and quail—was both consumed at home and marketed in the towns.

Hunting remained important into the 1850s. The last bison herd in the Delta was exterminated by the 1840s, and in short order, elk were hunted to extinction. The deer population—a major source of meat in the first quarter of the century—remained viable. Deer camp, a nineteenth-century male institution, featured male cooking, usually in the form of stews. Albert Pike, a noted gourmand, had his own special formula that was much revered.

During his tenure at Little Rock’s Arkansas Advocate, Pike advocated expanding and improving food choices. Central to his campaign was the tomato. Southern almanacs —a vital feature in the rural economy for a century—told farmers when and how to plant. These almanacs offered planting instructions on tomatoes from the start of the nineteenth century, and early Arkansas newspapers seasonally ran advertisements for tomato seeds as well as various squashes, turnips, cabbages, and other garden staples. Nurseries appeared by the 1840s and offered the various apple, peach, pears, cherry, and grape seedlings.

By the 1850s, grist mills spread across the Ozarks, using the vertical water wheel as the source of power. In the lowlands, oxen turned the machinery. In the fall, other machinery ground sorghum for making molasses. Honey, found from European bees that had moved west, and molasses, rather than white refined sugar, were the major sources of sweetening.

Arkansas was linked to the rest of the world by steamboats after 1822. Hence the stores stocked fine wines and liquors, as well as imported food. Canning, a new food processing system, appeared in Arkansas in the 1850s and was promoted by Fayetteville (Washington County) editor William Minor Quesenbury.

Food on the plantations and that on the upland farms was similar. However, planters bought salt pork and corn meal on the open market. Still, one plantation maintained a full-time hunter, and orchards and home gardens were standard. Fish was also important. Okra spread from the slave quarters to the big house on the plantations and hence throughout the state. Two defining Southern elements in plain cooking were the use of grits instead of potatoes and the sweetening—and, in the twentieth century, icing—of tea.

The Civil War created major and lasting disruptions. Many of the grist mills were destroyed during the war and not rebuilt until peace and population returned to the region. Herdsmen were major losers, and it took decades for them to regain their chief source of wealth. The destruction of fences (used by soldiers for firewood) and the wide-scale looting produced starvation and flight.

The post–Civil War years saw major changes in Arkansas foodways. Instead of open fireplaces, the cast-iron kitchen range or the coal-oil range modernized the cooking process. Perhaps the main benefit was the increased convenience in using the oven. In place of the generalized instructions of pre-war cookbooks (a “moderate oven,” a “tea cup,” or a “coffee cup”), exact measurements appeared. Middle-class Arkansans increasingly came to rely on printed sources for recipe ideas. One of the first editors to reprint these sources was Jacob Frolich at the White County Record in Searcy (White County), who in the 1870s was promoting strawberry production in the area. Country folk persisted using the older terminology for food instructions, calling them “receipts.” Locally produced cookbooks in the twentieth century mixed home remedies along with food instructions.

The first known Arkansas cookbook, Chicora’s Help to Housekeepers, published in Little Rock in 1891, was also one of the last still using the paragraph system of writing recipes. Hence, instead of an exact amount, the housewife making Mock Turtle Soup was given this instruction: “Remove the brains from a calf’s head.” The interested reader may also find catsup recipes made from cabbage or gooseberries.

The entry of railroads into Arkansas further affected foodways. Not only were more out-of-state foods available, but Arkansans could raise crops to sell out of state. Strawberries, peaches, apples, and watermelon were among the fruit crops, while fresh game and commercially harvested fish headed north to St. Louis, Missouri, and Chicago, Illinois. The age of the robber barons brought the discrepancy in food into sharp contrast. On the one hand, this period was the golden age for formal banquets, which attained previously unparalleled status when former U.S. president Ulysses S. Grant visited Little Rock in 1880. Group meetings similarly were occasions for gastronomic displays. In 1902, the nation’s leading press trade group, the National Editorial Association, met at the Eastman Hotel in Hot Springs (Garland County). The banquet cost $10 a plate ($233.59 in 2007 dollars) and included seven different wines on the menu. “A number of editors became unduly noisy,” and a fight broke out between a Northern publisher and a waiter, with the publisher landing in the hospital. On the other hand, the poorest sharecroppers and those working in lumber camps were susceptible to pellagra, a crippling and ultimately fatal disease later discovered to be caused by niacin deficiency. Pellagra victims often became inmates in the state insane asylum, but pellagra broke out there as well due to the lack of fresh vegetables at the institution.

By the 1890s, commercial canning plants invaded the state. Canners typically put up whatever was grown, and the seasonal range of products started with strawberries and included green beans, cabbage, blackberries, and especially tomatoes. By the 1920s, tomatoes were called the red gold of the Ozarks and were packaged in a variety of forms, including whole tomatoes, sauces, and catsup. Similarly, many farm families increased their ability to feed themselves through home canning. In contrast, the sharecroppers and tenant farmers, who came to account for about half of Arkansas’s farming families, often had no such access to these food enrichment resources. A southwest Arkansas cemetery unearthed and analyzed in the twentieth century gave startling proof of massive malnutrition. Virtually every slave narrative included the observation that food was better and more “secure” before the Civil War.

Arkansas was not much affected by late nineteenth-century immigration, and the rural nature of the state kept ethnic foods from attracting wider audiences. One scholarly study showed that Perry County’s Germans lost their food heritage over time, while the county’s Italians retained theirs. (One underlying reason was that anti-German sentiment during World War I undermined the integrity of the nation’s German community and hence its food; since Italy fought on the Allied side, Italian food, notably macaroni and spaghetti—but not pizza at this time—became acceptable.) Tontitown (Washington County) later capitalized on its Italian heritage by creating ethnic restaurants that drew customers from all over northwest Arkansas, eastern Oklahoma, and southwest Missouri. Ethnic food often endured because it was connected with religious and cultural traditions. Ethnic groups introduced vegetables not previously known as well as recipes that often differed in preparing common items.

Although not until the 1920s at Bauxite (Saline County) did a defined Hispanic population appear in Arkansas, tamales spread into the state in the late nineteenth century. The “Great Tamale War” in Augusta (Woodruff County) decimated the town’s stray dog population. Ironically, it was an Italian restaurant, Pasquale’s, in Helena (Phillips County), that was the best-known producer of this product. Perhaps the best example of assimilation was that town’s leading fruitcake maker, Habib’s (pronounced “hobbies”), founded by a Lebanese immigrant. The greatest food challenge was for the state’s Jewish population. Reform Judaism, the variety most seen in Arkansas, dropped the strict kosher requirements, but a sentimental attachment to traditional Jewish food remained and merged into the Southern mainstream. Catholic influence was seen after the 1940s when public school cafeterias became the norm, and many Protestant children discovered that Friday was fish day. Fish also figured in Lenten food preparation, and in time, fish dinners (invariably fried) were served by the Catholic men’s group, the Knights of Columbus. Similarly, central Arkansas’s Greek community celebrated its religious food heritage with goat and lamb. The arrival of the Vietnamese after a failed war brought in spring rolls and other delicacies that made their way into expanding cultural food options.

Twentieth Century

Town foodways were revolutionized in the early twentieth century. Three critical elements were the near universality of year-round ice, thus leading to food preservation in the “ice box,” a term whose use carried on even after electricity replaced ice boxes with refrigerators. Milk use increased dramatically, and recipes requiring “soured milk” passed into oblivion. Second, cities and towns built municipal water and sewer systems. Running water became a permanent feature of the kitchen as the former dry sink gave way to a double-water outlet of hot and cold water. Finally, the wood or coal-fired kitchen range was replaced by those operating from one of three energy sources: electricity, bottled gas (propane), or natural gas.

Equally important were the implications of the germ theory. The old meat market, where game and beef hung on hooks until the smell and the flies rendered it uneatable, gave way to bacteria testing and food safety standards. Beginning in 1910, Arkansas began enacting health and sanitation laws, including restaurant and hotel inspection. Inspection and enforcement, though, remained limited. One gubernatorial candidate during World War I even blamed the Germans for giving him food poisoning and interrupting his campaign.

After 1917, federal programs run from the county extension offices directly impacted food preparation. Women trained in nutrition science brought food education directly to farm women. Numerous extension clubs flourished beginning in the 1920s. Newspapers initiated food sections and advertised cooking schools. Further changes came during the Great Depression when extension agents established community canning centers where women could use pressure canning and thus put up entire dinners using meat and other low-acid foods that were unsafe using the boiling water method. Frank Robins at the Conway (Faulkner County) Log Cabin Democrat observed in 1938, “I might talk at length of how the quality and tastefulness of this country food has improved during the past two decades as a result of home instruction and home demonstration work.”

Despite these many changes, across much of the state, food preparation systems dating back to before the Civil War endured. Central to upper- and middle-class kitchens was the African-American cook. Most until the twentieth century were illiterate and thus did not work from written recipes. Often, they had learned their skills from their mothers and had been in the kitchen since infancy. After the Civil War, the kitchen was frequently a battleground between white women trying to modernize and their cooks resisting changes. Another battleground was fought in the dining room. In rural areas, men and even the boys were fed first by women, who were not permitted to eat until the men had been satisfied. The fight for sexual equality in Arkansas often began at home as women challenged these inherently demeaning rules of life.

By the early twentieth century, the extermination of the passenger pigeon and the federal and state game laws literally took game off the table, especially in commercial settings. High-class food could be found at a price in Hot Springs and in a few hotels and restaurants. In addition, Arkansas, in the form of Alice French (a.k.a. Octave Thanet) of Clover Bend (Lawrence County), had a woman whose “high class southern cooking—turkeys stuffed with chestnuts, quail fried exquisitely, and all manner of gorgeous pastry,” as well as the best of wines, earned the praise of national columnist William Allen White. However, it was more typical of Arkansas that the children attending meetings of the Arkansas Press Association in Hot Springs encountered shrimp for the first time in their lives.

Meanwhile, in rural areas, courtship and food preparation went together in a ritual known as pie auctions. Every young woman was expected to have mastered cooking skills and be willing to compete with others for top honors, whether at the county fair or at a local fundraiser. Further, her beaus were expected to honor her work by bidding whatever it took to win the pie or cake. While America’s upper class sang of “the hearts that were broken, after the ball,” similar heartbreaks sometimes accompanied these rural events.

World War II ushered in major challenges to the existing foodways. As men went off to war, and as population fled the state for jobs elsewhere, many traditional ways were abandoned. All during the century, the food industry had been moving away from raw products and toward processed foods. As women took jobs outside the home, it was easier to serve cereal rather than cook a traditional breakfast. Meanwhile, although the war interrupted the rural electrification of Arkansas, after the war, the process continued apace. Among the new appliances often purchased was a freezer, and traditional ham-curing practices faded out. Electrification offered some farmers a chance to increase their dairy herds by using electric milking machines, but conversely many abandoned the family cow as fresh milk became easier to buy. Home canning began a decline, and a new wave of “instant” products reduced food preparation time.

In the 1930s, Arkansas came to specialize in the mass production of turkeys and chickens. Mass egg-farming ended the farm wife’s egg money. Increasingly, cooking skills consisted only in combining pre-mixed ingredients. Once housewife-prized recipes—notably for biscuits, cookies, cakes, and pie shells—came first out of a box and then from the grocery store freezer case.

By the 1960s, fast food restaurants began to lure Arkansas customers. One now-defunct Arkansas-based hamburger chain, Minute Man, is commemorated by a marker on a Little Rock sidewalk. Another temporary success story was TCBY, a franchising yogurt company whose corporate presence in Little Rock consisted of a highly visible downtown office building that no longer bears the company’s name.

The arriving chains greatly altered the ways Arkansans thought about food. Prior to the 1960s, pizza was virtually unknown, and Mexican and Chinese restaurants were even rarer. By standardizing product names, reducing exotic ingredients and strong spices, and luring the young, restaurants moved away from plain “American” food. Often, chains chose to package their wares in buffet lines. One reason for the staggering obesity problems of the twenty-first century was the move from food scarcity prior to 1950 to food excess by 1980. As obesity and diabetes reached crisis proportions even among children, the state legislature mandated highly controversial body mass assessments of students.

Dining out increased in importance after 1940. Places of some regional note included Habib’s in Helena, where the second floor was a ballroom; Constantino’s in Fort Smith (Sebastian County); the AQ Chicken House in Springdale (Washington County); the Red Apple Inn and Country Club near Heber Springs (Cleburne County); and a host of barbecue places that included Craig’s in DeValls Bluff (Prairie County) and Couch’s in Nettleton (now Jonesboro in Craighead County). The Bohemia in Hot Springs was the most enduring Central European cuisine establishment.

In larger towns, a few higher-scale restaurants emerged, with Jacques & Suzanne’s in Little Rock in 1975 being a flagship effort. By 2006, variety in Arkansas was extensive, especially in Little Rock, Hot Springs, Eureka Springs (Carroll County), and Fayetteville. Varieties came to include Thai, Vietnamese, catfish, barbecue, multiple varieties of Chinese, Italian, German, Czech, Indian, and even vegan. By 2007, Mexican restaurants probably outnumbered all others.

Perhaps no aspect of foodways underwent more changes than that related to alcohol. In the nineteenth-century saloon, drinking was done standing up, and a “free lunch” provided food. Prohibition closed saloons for good, and the cocktail lounges that followed often served food, but with patrons seated instead of standing. Some persons argued that more excessive drinking resulted when patrons were seated. Across the state, the availability of alcohol varied, being almost unobtainable legally in Ozark counties. Starting in 1969, the state permitted private clubs in dry counties, but upper-end restaurants were impractical financially without being able to serve alcohol. The “town” of Wiederkehr Village (Franklin County) came into existence in 1975 so that a wine company could run a restaurant that would serve its wine. With more than half the counties in Arkansas being “dry,” alcohol (and hence indirectly food) remained controversial.

Conclusion

By 2006, Arkansans took more than half their meals out of the home. One exchange student was amazed when, during an entire semester, her host family never sat down to a home-prepared meal. As many modern middle- and lower-class families witnessed the end of the stay-at-home mother, home food production continued to decline. The University of Arkansas Cooperative Extension Service (UACES) dropped canning from its website.

Ironically, the past fifty years also witnessed an explosion of locally produced cookbooks. The less people cooked, the more books they bought about cooking. In general, local cookbooks came into three categories. The first was the personal cookbook, either from a single cook or a single restaurant. The second was put together as a fundraising event from a church or organization in which numerous persons contributed their favorite recipes. Finally, there were thematically arranged cookbooks. These ranged from a masterly study of Dutch oven cooking to one devoted, perhaps facetiously, to Arkansas road kill. And one Arkansan produced a thousand-page tome on vegetarian cooking. The cookbook collection at UA in 2011 ran to 1,200 volumes, with a Stamps (Lafayette County) Presbyterian church publication of 1915 being the earliest copyright.

Food figured prominently in most of Arkansas’s festivals. Indeed, some were organized around specialized food components. Competitions for barbecue and chili were common. No state politician could avoid attending the Gillett Coon Supper. Virtually every county had some kind of festival with food being an important function: the Greek Food Festival in Little Rock; the Altus Grape Fest in Altus (Franklin County); the Arkansas Rice Festival in Weiner (Poinsett County); a spinach festival in Alma (Crawford County); a gumbo festival in West Memphis (Crittenden County); a pickle festival in Atkins (Pope County), home of the famous fried dill pickle; and the Hope Watermelon Festival in Hope (Hempstead County). Tomatoes, purple hull peas, peaches, and crawfish also are at the center of various local events. One measure of the power of food came when the racial polarization over food vendors hit the King Biscuit Blues Festival in Helena. In 2017, the Arkansas Food Hall of Fame was established.

Since all foodways continue to evolve, only a few conclusions tentatively may be reached. Arkansans raise an ever-diminishing supply of their own food. In the richest agricultural part of the state, the Delta, only about five percent of the food is not imported. Arkansas has seen the collapse of the peach and apple orchards as well as the near abandonment of home gardening and home food preservation. Whatever the convenience, the changes of the past fifty years have not made Arkansans healthier. The state’s high ranking in heart disease is directly traceable to a diet of meat, fried foods, sugars, and uncontrolled use of the salt shaker. Even Arkansas’s equally high ranking in dental-related problems is tied in part of food. Governor Mike Huckabee set an example by reversing his weight gain and by engaging in vigorous exercise. However, attempts to address these problems in the public schools, where the onset of adult diabetes in children has become a chronic problem, have been met with opposition.

For additional information:

Abbott, Shirley. Womenfolk: Growing Up Down South. New Haven: Ticknor and Fields, 1983.

Arkansauce: The Journal of Arkansas Foodways. Fayetteville: Special Collections Department of the University of Arkansas Libraries (2011–).

Arnold, Morris S. Colonial Arkansas, 1686–1804: A Social and Cultural History. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1991.

Ashley, Liza (as told to Carolyn Huber). Thirty Years at the Mansion: Recipes and Recollections. Little Rock: August House, 1985.

Chen, Diana. “Got Breadfruit? Marshallese Foodways and Culture in Springdale, Arkansas.” PhD diss, University of Arkansas, 2018. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2825/ (accessed July 6, 2022).

Eifling, Sam. “What Do Arkansans Eat?” Oxford American, March 2010, pp. 56–58.

Dragonwagon, Crescent. Passionate Vegetarian. New York: Workman Publishing, 2002.

Featherstonhaugh, George W. Excursion Through the Slave States from Washington on the Potomac to the Frontier of Mexico; with Sketches of Popular Manners and Geological Notices. New York: Negro Universities Press, 1968.

Ferris, Marcie Cohen. The Edible South: The Power of Food and the Making of an American Region. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014.

———. Matzoh Ball Gumbo: Culinary Tales of the Jewish South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005.

Fountain, Sarah M., ed. Sisters, Seeds, & Cedars: Rediscovering Nineteenth-Century Life through Correspondence from Rural Arkansas and Alabama. Conway: University of Central Arkansas Press, 1995.

Gates, C. Laine, Justin M. Nolan, and Mary Jo Schneider. “The Politics of Traditional Foodways in the Arkansas Delta.” In Southern Foodways and Culture: Local Considerations and Beyond, edited by Lisa J. Lefler. Knoxville, TN: Newfound Press, 2013.

Giddings, Judy, and June Simmons. Arkansas Favorites…Recipes, Parks, Places. Hot Springs: 1991.

Grisham, Cindy. A Savory History of Arkansas Delta Food: Potlikker, Coon Suppers and Chocolate Gravy. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2013.

“Let’s Eat: A Collection of Arkansas Menus.” Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, Central Arkansas Library System. https://robertslibrary.org/arkansasmenus/ (accessed July 3, 2023).

Malone, Ruth Moore, and Bess Malone Lankford. Arkansas Classic Country Cookbook: Traditional and Contemporary Recipes. N.p.: 1994.

McKee, Gwen, and Barbara Moseley. Best of the Best: Selected Recipes from Arkansas’ Favorite Cookbooks. Brandon, MS: Quail Ridge Press, 1992.

Morein, Alyssa Shirley. “Domestic Policy; Homemaker’s Guide Books, 1890–1920.” White River Journal, January 2005.

Pascal, Olivia. “Food, Power, and Place in Northwest Arkansas.” Scalawag, January 6, 2020. https://scalawagmagazine.org/2020/01/arkansas-southern-foodways-alliance/ (accessed November 11, 2021).

Ragsdale, John G. Dutch Oven Cooking. Houston: Pacesetter Press, 2006.

Randolph, Vance. The Ozarks: An American Survival of Primitive Society. New York: Vanguard Press, 1931.

Reed, Jennifer Barnett. “Take It Slow.” Arkansas Times. December 6, 2007, pp. 12–14, 16.

Robinson, Kat. Arkansas Dairy Bars: Neat Eats and Cool Treats. Little Rock: Tonti Press, 2021.

———. Arkansas Food: The A to Z of Eating in the Natural State. Little Rock: Tonti Press, 2018.

———. A Bite of Arkansas: A Cookbook of Natural State Delights. Little Rock: Tonti Press, 2020.

———. Classic Eateries of the Arkansas Delta. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2014.

———. Classic Eateries of the Ozarks and Arkansas River Valley. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2013.

Rowe, Erin. An Ozark Culinary History: Northwest Arkansas Traditions from Corn Dodgers to Squirrel Meatloaf. Charleston, SC: American Palate, 2017.

Schrock, Earl F., Jr. “Traditional Arkansas Foodways.” In An Arkansas Folklore Sourcebook, edited by W. K. McNeil and William M. Clements. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1992.

Spears, Robyn. “Arkansas Aprons: Food, Power, and Women in Arkansas, 1857–1891.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2020. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/3706/ (accessed July 6, 2022).

Stamps Presbyterian Cook Book: Containing Valuable Recipes, Menus, Tables of Measure, and Other Useful Information. Texarkana: Four States Press, 1915.

Tebbetts, Diane. “Food as an Ethnic Marker.” Pioneer America Society Transactions 7 (1984): 81–88.

Thomas, Ruby C. Feasts of Eden: Gracious Country Cooking from the Red Apple Inn. Little Rock: August House, 1990.

Trubitt, Mary Beth. “Ancient Indian Foodways: a View from the Jones Mill Archeological Site.” The Record (2011): 127–137.

Ulmer, Amy. “Fat Shaming the Delta: How Social Issues Become Individualized via ‘Delta Obesity Talk’.” PhD diss., Arkansas State University, 2018.

Van Buskirk, Kathleen. “Winds of Change Blew Over the Ozarks.” Ozarks Watch 7 (Spring 1994): 1–7.

Veteto, James R., and Edward M. Maclin, eds. The Slaw and the Slow Cooked: Culture and Barbecue in the Mid-South, edited by James R. Veteto and Edward M. Maclin. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press, 2011.

Wallach, Jennifer Jensen. “What Is the Delta from a Foodways Perspective?” In Defining the Delta: Multidisciplinary Perspectives on the Lower Mississippi River Delta, edited by Janelle Collins. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2015.

Michael B. Dougan

Jonesboro, Arkansas

Arkansas Wet/Dry Counties

Arkansas Wet/Dry Counties  Baker's Cafe

Baker's Cafe  Bootlegged Liquor

Bootlegged Liquor  Corner Cafe

Corner Cafe  Cooking Crawfish

Cooking Crawfish  Crawfish

Crawfish  Dutch Oven

Dutch Oven  Dutch Oven

Dutch Oven  Dutch Oven

Dutch Oven  Ed Walker's Drive-in and Restaurant

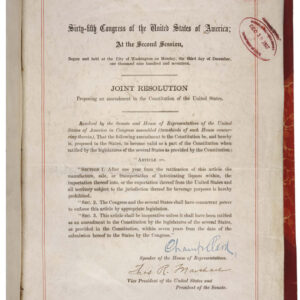

Ed Walker's Drive-in and Restaurant  Eighteenth Amendment

Eighteenth Amendment  Fordyce on the Cotton Belt Festival Cake Train

Fordyce on the Cotton Belt Festival Cake Train  Franke's Cafeteria

Franke's Cafeteria  Grapette Jingle

Grapette Jingle  Grapette Brochure

Grapette Brochure  Carl Hall

Carl Hall  Hog Butchering

Hog Butchering  Joe’s Cafe

Joe’s Cafe  Kelley’s Grill

Kelley’s Grill  Kindervater's Butcher Shop

Kindervater's Butcher Shop  Lackey's Hot Tamales

Lackey's Hot Tamales  Mena Meat Market

Mena Meat Market  Minute Man, Jacksonville

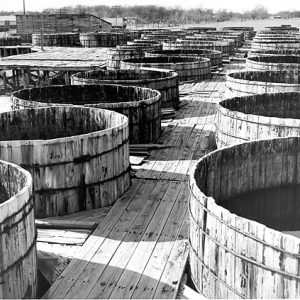

Minute Man, Jacksonville  Pickle Barrels; 1955

Pickle Barrels; 1955  Popeye Statue

Popeye Statue  Pulaski Tech Culinary School Entrance

Pulaski Tech Culinary School Entrance  Rogers Historical Museum Exhibit

Rogers Historical Museum Exhibit  Salt Kettle

Salt Kettle  Star of India

Star of India  Tamales

Tamales

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.