calsfoundation@cals.org

Convict Lease System

The convict lease system was a way of operating state prisons adopted by Arkansas in the mid-nineteenth century. The Arkansas system mirrored that of other Southern states during this period and reflected the desire to reduce the cost and administrative problems of the state’s prisons. While the system achieved its economic goals, it was typified by corruption and the abuse of prisoners, problems that ultimately brought about its abolition.

In Arkansas, the convict lease system originated during the Reconstruction era when, in 1867, the state contracted with the firm of Hodges, Peay, and Ayliff to provide work for prisoners in the penitentiary at Little Rock (Pulaski County). The state agreed to pay the company thirty-five cents a day for the convicts’ support and also purchased the machinery to establish a factory within the prison. Managing the prison apparently was lucrative, and until 1873, several other individuals secured the management contract, including Asa Hodges, a Little Rock brick and wagon manufacturer and prominent Republican politician, who took over the prisons in 1869. Typically, the prison lessee not only provided work within the prison walls but also subcontracted prisoners to work throughout the area.

In 1873, as Reconstruction came to an end, the state legislature revised its program of prison leases and ended payments made to the lessee to support the prisoners. That year’s contract with John M. Peck and his silent partner, Colonel Zebulon Ward, leased prisoners to Peck and required that the lessee furnish labor, food, clothing, and housing for them. The state was to have no expenses. In 1875, Ward bought out Peck and held the prison contract until 1883. Ward profited greatly from his contract, benefitting from the rapid increase in the state’s prison population from 1876 to 1882 after the legislature’s passage in 1875 of a law that made the theft of any property worth two dollars or more punishable by one to five years of imprisonment. Ward also received the contract to build a major expansion of the state prison, using convict labor.

Another major change in the nature of the convict lease system came in 1883. In the lease negotiated that year, Arkansas adopted the practice of other Southern states by requiring the lessee to pay the state for convict labor. The lease became a major source of income for the state, making the system particularly difficult to eliminate. The 1883 lease was secured by J. P. Townshend and L. A. Fitzpatrick, Helena (Phillips County) planters, who later maintained the contract with Met L. Jones as a corporation, the Arkansas Industrial Company. The Arkansas Industrial Company continued to give work to some prisoners at the prison, but hundreds were sent outside the walls to work for subcontractors. An 1890 prison report indicated that those working in camps around the state were laboring on plantations, building railroads, and mining coal in the Coal Hill (Johnson County) area of western Arkansas.

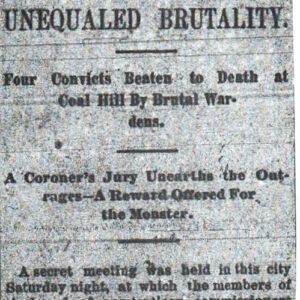

The convict lease system led to considerable corruption. In its early days, lessees took state payments and put little into the maintenance of prisoners. Later, contractors and subcontractors saw prison labor as a means of securing cheap workers who did not need to be provided proper care. Problems became so great that, in 1888, a legislative committee investigated conditions at the Coal Hill camp; beginning in 1890, a prison inspector visited and reported on conditions in all of the camps. These examinations indicated that prisoners suffered from overcrowding, inadequate food and housing, and poor clothing. Health and hygiene facilities were non-existent. In addition, they were subjected to violent physical punishment and abuse by the guards. Contractors also failed to provide security for the prison camps, and escapes became commonplace.

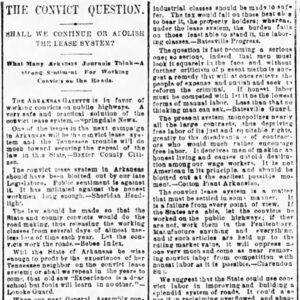

Concern with conditions in the camps became an issue in state politics after 1888, with farmer movements such as the Agricultural Wheel and the Farmers’ Alliance, along with the Knights of Labor, calling for the end of the system. The legislature made an initial attempt to improve circumstances in 1893 when it did not renew the lease to the Arkansas Industrial Company. Unfortunately, state financial resources were inadequate to create a system that allowed the state to take over full maintenance of the prisoners. Instead, while the state assumed control over the inmates, it began its own subcontracting system by placing prisoners on farms as sharecroppers, at work on the railroads, and in other business enterprises around the state.

All the abuses seen in 1888 and 1890 continued as the state placed its prisoners under the control of private contractors, and in 1909, Governor George Donaghey, elected as a progressive Democrat, asked for the lease system to be abolished in his first message to the legislature. Legislators favored the reform but refused to appropriate the money necessary to create a prison farm big enough to employ all of the state’s prisoners. In 1912, Donaghey resolved to end the system and determined how many prisoners could be placed on the existing state farm near Grady (Lincoln County); he then paroled enough prisoners to reduce the population to that number. Donaghey effectively ended the system, although the legislature’s purchase of land for a larger prison farm in Jefferson County, now known as the Tucker Unit, formally halted the leases the next year.

For additional information:

Delevingne, Lawrence, and Tom Lasseter. “Slavery’s Descendants, Part 6: Heirs of Power.” Reuters, December 13, 2023. https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/usa-slavery-families/ (accessed December 13, 2023).

Ledbetter, Calvin R., Jr. “The Long Struggle to End Convict Leasing in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 52 (Spring 1993): 1–27.

Mancini, Matthew J. One Dies, Get Another: Convict Leasing in the American South, 1866–1928. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1996.

Zimmerman, Jane. “The Convict Lease System in Arkansas and the Fight for Abolition.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 8 (Autumn 1949): 171–188.

Carl H. Moneyhon

University of Arkansas at Little Rock

Penal Systems

Penal Systems Prison Reform

Prison Reform Convict Lease Article

Convict Lease Article  Convict Lease Article

Convict Lease Article  Convict Lease System Article

Convict Lease System Article

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.