calsfoundation@cals.org

Steamboats

The steamboat played an important role in Arkansas from the earliest days of the Arkansas Territory. Before being superseded by the railroad in the post–Civil War era, steamboats were the primary means of passenger transport, as well as moving raw materials out of Arkansas and consumer goods into the state.

The inland rivers steamboat, invented in the Mississippi River Valley in the first half of the nineteenth century, eventually connected every person on or near a stream to the larger world. The first major historian of the steamboat, Louis Hunter, saw the steamboat as the “most notable achievement of the industrial infancy” of the United States, not to mention the chief technological means by which the frontier advanced and by which steam power was introduced and spread in the United States. Building and supplying steamboats with hulls and machinery provided the infrastructure that pushed the United States’ transition from the “wood age” to the “iron age.”

In 1820, the steamboat Comet made it to Arkansas Post (Arkansas County); two years later, the Eagle was the first to visit Little Rock (Pulaski County) on its way to what is now Russellville (Pope County) with a load of supplies for Dwight Mission. The Arkansas Gazette reported numerous steamboats operating regularly on Arkansas waters even in the 1820s, including the Robert Thompson, Allegheny, Spartan, Industry, and Catawba. By 1829, the Laurel had reached Pocahontas (Randolph County) on the Black River, and two years later, Batesville (Independence County) on the upper White River was reached by the Waverly. The Ouachita River had its Dime, and even the Red River Raft was breached by the late 1830s. By about 1875, steamboats had reached everywhere in the state, up the Little Red River, into the Fourche La Fave River, up the St. Francis River and Bayou Bartholomew, and eventually up the Buffalo River as far as Rush (Marion County). The keelboats that had once supplied these towns were supplanted by these vessels that could reach almost anywhere in the state with cargoes of factory goods and foodstuffs, along with emigrants and travelers, and then go downstream with cotton or subsistence staples.

It is difficult to find details on most of these steamboats. After the mid-nineteenth century, boats were required to be registered and their boilers certified, but even these requirements documented only such details as name, length, width, depth of hull, sometimes the number of boilers and the diameter of cylinders in the engines, and something called “tonnage,” which was calculated in different ways at different times. The earlier boats are especially poorly known, partly because the inland rivers steamboat had to be created to deal with unique conditions on inland rivers, a process that was poorly recorded. Rapid progress involved numerous false steps, hand labor, and experiment tempered by experience. Rapid development also took place in building and controlling steam engines to make them more reliable and safe, with the concurrent development of all the associated regulations and legal protections.

The form of the steamboat itself came into being particularly in the 1820s and 1830s. A steamboat is different from the deep-water, deep-draft vessel that has cargo, quarters, and everything else deep in the hull. The new form was simply a long, narrow, shallow pontoon upon which cargo was stacked and cabins were built higher and higher. Some cargo could be placed in the hull, but the engines and boilers sat on the main deck; passengers’ cabins and the salon were on the second or “boiler” deck with perhaps a “Texas” deck above that for the crew; and the pilot house perched at the front of the stack for visibility. The hull, much like a bridge, had to be reinforced with an extensive truss system, known as “hog chain” and consisting of long runs of wrought-iron rods over stout “sampson” posts, both along the length, as much as 350 feet, and across the width, up to forty feet plus overhanging “guards” that made the main deck even wider than the hull. The wrought-iron rods were fitted with enormous turnbuckles, and by tightening or loosening these turnbuckles, the flexible hull could even be “walked” over shallow sand bars.

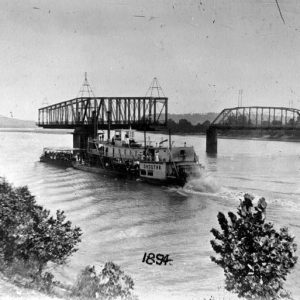

There were variations in placement of the paddlewheels. Putting them on each side of the hull, as in those boats known as “sidewheelers,” made for smoother passenger travel and a bit easier steering, but the paddlewheels were outside the lines of the hull, leaving them vulnerable and making the vessel much wider. The sternwheeler put the paddlewheel at the back, creating a narrower vessel as well as protecting the fragile paddlewheel by hiding it at the rear of the hull. The sternwheeler eventually proved more efficient at pushing barges, and it was the sternwheeler form that survived the loss of the passenger trade brought on by the spread of railroads after the 1870s; in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, sternwheelers were used for towboats.

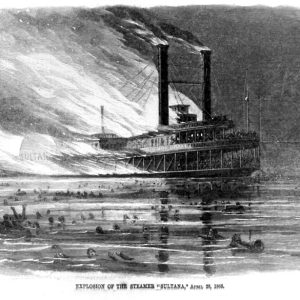

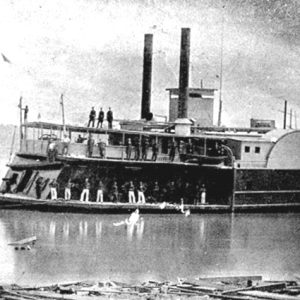

These wooden-hulled steamboats were vulnerable, and their lives were often short. The most frightening losses were from boiler explosions due to abuse, clogging by muddy river water, or design weaknesses. One of the most famous boiler explosions occurred on the sidewheel steamboat Sultana. The only photograph of the Sultana was taken during a short stop at the waterfront at Helena (Phillips County) on April 26, 1865. The photograph shows that the boat was astonishingly overloaded—in a vessel 260 feet long and forty-two feet wide, built in 1863 for 300 or so passengers, thousands of people could be seen, nearly all of them Union soldiers recently released from Confederate prisoner-of-war camps. Not long after the boat stopped briefly at Memphis, the boilers of the Sultana exploded near Mound City (Crittenden County) in the middle of the night on April 27. Approximately 2,000 to 2,300 people were killed. This remains the worst maritime disaster in North America. Many times the disaster was less spectacular, the result of accidentally holing the hull by ramming into submerged log, but the result was still loss of the vessel; most of the time, at least some of the cargo and steamboat machinery was salvaged.

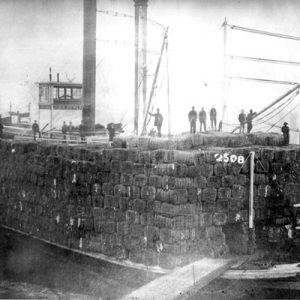

In spite of their vulnerability, hundreds of sternwheelers and sidewheelers of various dimensions were an integral part of daily life in Arkansas for most of the 1800s, certainly from 1830s into the 1880s, when the network of railroads finally reached maturity. Any factory goods from ceramic tablewares to pianos traveled at least part of the way by steamboat, and even for isolated farmsteads, the wagon journey at the end was only a few miles from the riverside landing to the house. Cotton, corn, livestock, wool, bricks, lumber, staves, logs, and other products traveled only a short way to the docks.

Steamboats played a role in tumultuous events as well, beginning with carrying troops and supplies in the early 1800s to Fort Smith (Sebastian County). In the 1830s, tens of thousands of Native Americans passed through Arkansas as part of Indian Removal, and many traveled on steamboats such as the Smelter, Thomas Yeatman, Reindeer, Little Rock, Tecumseh, and Cavalier, or on the keelboats often towed by these vessels. Moreover, much of the crew on antebellum steamboats were slaves.

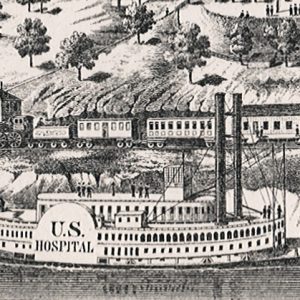

During the Civil War, both Union and Confederate forces exploited steamboats for rapid communication and transport of troops, horses, and supplies on Arkansas waters. Little Rock, Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), DeValls Bluff (Prairie County), and Helena became major re-supply centers and shipping points, first by the Confederacy, then by the Union. Civilian vessels were chartered; in the case of the Homer, the Confederacy made use of it until its capture by the Union and scuttling in the Ouachita River in April 1864 at Camden (Ouachita County). Bombardment of Confederate positions on land by Union gunboats was an important factor in the capture of St. Charles (Arkansas County) on the White River in June 1862, the destruction of Arkansas Post (Arkansas County) in January 1863, and the defense of Helena in July 1863. The Engagement at St. Charles included the scuttling of three steamboats by Confederates in a vain attempt to block the upstream advance of the Union fleet. The capture of Little Rock in September 1863 saw the sinking of more Confederate vessels, including the gunboat Pontchartrain. Throughout the war, Union-chartered steamers and specially built tin-clad and iron-clad warships were fired on regularly from the shore, and Confederates even managed to capture and burn the tin-clad Queen City at Clarendon (Monroe County) in June 1864.

After the Civil War, some of the biggest-ever sidewheel steamboats were built for use on the Mississippi, but by the 1890s, passenger travel had largely ended. Indeed, passage on many rivers was made more difficult simply by the construction of many bridges for the trains. However, improvements in sternwheel maneuverability and increases in power—combined with increasing improvement of the waterways by dredging, snag removal, and electric light channel marking—made the larger rivers such as the Arkansas, the lower White, and Red efficient for the transport of bulk cargoes such as iron, grain, construction materials, chemicals, gravel, sand, and coal. Water transport is still common today, when a diesel-powered all-steel towboat can push twelve to thirty-six steel barges, and just one steel barge can carry the equivalent of fifteen large hopper-type railroad cars or fifty-eight semi-trailers. Even a modern sternwheel passenger steamboat sometimes plies the Arkansas River, such as the Delta Queen, built in 1924–1927 for excursions on the Sacramento River in California and rebuilt for the Mississippi River system in 1947.

The chart below lists some of the steamboats that were notable in Arkansas history. A list of those involving fatal accidents can be found at the Steamboat Disasters entry.

| Steamboat Name | Significance for Arkansas | Date(s) |

| Comet | First steamboat to ascend the Arkansas River, reaching Arkansas Post | March 31, 1820 |

| Eagle | First steamboat to reach Little Rock (Pulaski County) | March 16, 1822 |

| Thomas Jefferson | Sank after hitting snag at Helena (Phillips County) | October 4, 1824 |

| Montezuma | Sank after hitting snag at Helena | February 28, 1829 |

| Laurel | First steamboat to ascend the Black River to Pocahontas (Randolph County) | 1829 |

| Waverly | First steamboat to ascend the White River to Batesville (Independence County) | 1831 |

| William Parsons | Snagged and sank at Little Rock | April 12, 1835 |

| Compromise | Snagged and sank at Little Rock | April 16, 1837 |

| Keystone | Burned and sank on the Mississippi River at Arkansas City (Desha County) | June 24, 1841 |

| Houma | Snagged and sank on the Red River at Fulton (Hempstead County) | September 28, 1842 |

| Arkansas | Snagged and sank on the Arkansas River at Lewisburg (Conway County) | March 29, 1844 |

| Rolla | Snagged and sank on the Arkansas River at Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) | November 17, 1845 |

| Republic | Snagged and sank at Lewisburg | June 12, 1846 |

| Admiral | Lost in collision on the Arkansas River at Clarksville (Johnson County) | December 28, 1847 |

| Alert | Snagged and sank on the Arkansas River | 1847 |

| Pilot | Snagged and sank on the Arkansas River | 1848 |

| Bayou Bouef | Foundered at Clear Lake | March 25, 1848 |

| Sallie Anderson | Burned and sank at Little Rock | September 24, 1849 |

| William Armstrong | Snagged and sank at Little Rock | November 1849 |

| Citizen | Snagged and sank on the Arkansas River | December 1850 |

| Philip Pennywit | Snagged and sank on the Arkansas River at Van Buren (Crawford County) | May 13, 1851 |

| John B. Gordon | Snagged and sank on the Arkansas River | June 8, 1851 |

| General Lane | Snagged and sank at the mouth of the St. Francis River | December 30, 1851 |

| Romeo | Snagged and sank on the Ouachita River at Champagnolle (Union County) | December 31, 1851 |

| Jefferson | Snagged and sank at Pine Bluff | February 26, 1852 |

| Cotton Plant | Burned and sank at Napoleon (Desha County) | May 22, 1852 |

| Emily | Snagged and sank on the White River | August 6, 1852 |

| May Queen | Snagged and sank 45 miles below Little Rock on the Arkansas River | August 13, 1852 |

| Preston | Snagged and sank on the White Oak Shoals of the Red River | May 4, 1853 |

| Youghiogheny | Snagged and sank on the White River | December 25, 1853 |

| Ringgold | Snagged and sank on the Arkansas River | February 1848 |

| Umpire No. 2 | Snagged and sank on the Arkansas River above Little Rock | August 1, 1854 |

| Garden City | Burned and sank 25 miles below Napoleon | January 14, 1855 |

| Luella | Sank in a collision on the White River | September 17, 1855 |

| Sangamon | Snagged and sank on the White River at St. Charles (Arkansas County) | February 12, 1856 |

| Young American | Snagged and sank on the St. Francis River near Linden (St. Francis County) | January 20, 1857 |

| Camden | Snagged and sank at Fulton | April 1857 |

| John Strader | Burned and sank on the Mississippi River above Gaines Landing (Chicot County) | November 18, 1857 |

| Exchange | Snagged and sank on the White River | January 13, 1858 |

| Jesse Lazer | Snagged and sank on the White River | January 1858 |

| Rough and Ready | Sank in collision at Napoleon | December 1858 |

| Dardanelle | Snagged and sank at Pine Bluff | February 6, 1859 |

| Trustee | Snagged and sank on the Arkansas River at Van Buren | February 18, 1859 |

| D. H. Morton | Snagged and sank on the Arkansas River at Dardanelle (Yell County) | March 11, 1859 |

| Resolute | Snagged and sank at Van Buren | April 10, 1859 |

| Grapeshot | Snagged and sank at Van Buren | June 10, 1859 |

| Return | Snagged and sank on the White River at DeValls Bluff (Prairie County) | July 28, 1859 |

| Irene | Snagged and sank at Little Rock | September 24, 1859 |

| Lucy Holcombe | Burned and sank at Helena | November 11, 1859 |

| Red Wing | Snagged and sank at Smith Cutoff | May 25, 1860 |

| Isaac Shelby | Snagged and sank on the Arkansas River at Swan Lake (Jefferson County) | June 21, 1860 |

| Interchange | Snagged and sank on the White River | October 1860 |

| Bridge City | Burned and sank at Napoleon | November 29, 1860 |

| Conway | Snagged and sank at Badgett Landing | December 15, 1860 |

| Julia | Snagged and sank on the Arkansas River | December 17, 1860 |

| A. H. Sevier | Snagged and sank at Pine Bluff | December 31, 1860 |

| Clara Dolsen | Auxiliary vessel for Confederate navy captured by Union navy in St. Charles Expedition and then used by Federals | 1861–1865 |

| Frontier City | Snagged and sank at Napoleon | January 4, 1861 |

| Aid | Snagged and sank on the St. Francis River | January 28, 1861 |

| S. H. Tucker | Rumors that it was taking reinforcements to U.S. garrison led to Little Rock Arsenal crisis | February 1861 |

| Quapaw | Snagged and sank at Little Rock | February 11, 1861 |

| Cedar Rapids | Snagged and sank at Douglas Landing | February 12, 1861 |

| William Henry | Snagged and sank on the Arkansas River at Fort Smith (Sebastian County) | June 2, 1861 |

| Lizzie Simmons | Steamboat converted to gunboat CSS Pontchartrain, later burned by Confederates during retreat from Little Rock | 1861-1863 |

| Southwester | Steamboat carrying U.S. supplies seized at Napoleon | January–February 1862 |

| Sunshine | Steamboat carrying U.S. supplies seized at Napoleon | January–February 1862 |

| Grosse Tete | Steamboat converted into gunboat CSS Maurepas | 1862 |

| Resolute | Steamboat used by Union forces | 1862–1865 |

| Mary Patterson | Steamboat scuttled to block the White River at St. Charles | June 17, 1862 |

| Eliza G. | Steamboat scuttled to block the White River at St. Charles | June 17, 1862 |

| Iatan | Used as Union transport in Eunice Expedition | August–September 1862 |

| White Cloud | Used as Union transport in Eunice Expedition | August–September 1862 |

| Lake City | Burned and sank at Carson Landing | December 8, 1862 |

| Era No. 6 | Burned by Union troops at Van Buren | December 27, 1862 |

| Frederic Nortrebe | Burned by Union troops at Van Buren | December 27, 1862 |

| Key West | Burned by Union troops at Van Buren | December 27, 1862 |

| Rose Douglas | Burned by Union troops at Van Buren | December 27, 1862 |

| Violett | Burned by Union troops at Van Buren | December 27, 1862 |

| Blue Wing No. 2 | Captured on the Mississippi River by Confederates, led to U.S. attack on Arkansas Post | January 1863 |

| Jacob Musselman | Captured on the Mississippi River by Union troops | January 11, 1863 |

| Grampus | Captured on the Mississippi River by Union troops | February 11, 1863 |

| Hercules | Steam tug captured on the Mississippi River by Union troops and burned | February 17, 1863 |

| Pike | Auxiliary vessel for Union navy, used in Napoleon Expedition | May 23–26, 1863 |

| Mill Boy | Floating gristmill used by U.S. in burning of Hopefield (Crittenden County), later snagged and sank | 1863–1864 |

| Kaskaskia | Captured on the Little Red River by U.S. troops | August 11, 1863 |

| Arkansas | Burned by Confederates during retreat from Little Rock | September 10, 1863 |

| Bracelet | Burned by Confederates during retreat from Little Rock | September 10, 1863 |

| Chester Ashley | Burned by Confederates during retreat from Little Rock | September 10, 1863 |

| Julia Roane | Burned by Confederates during retreat from Little Rock | September 10, 1863 |

| Little Rock | Burned by Confederates during retreat from Little Rock | September 10, 1863 |

| St. Francis No. 3 | Burned by Confederates during retreat from Little Rock | September 10, 1863 |

| Tahlequah | Burned by Confederates during retreat from Little Rock | September 10, 1863 |

| Diurnal | Burned and sank at St. Charles | September 12, 1863 |

| Robert Fulton | Burned and sank at Union Point on the Red River | October 7, 1863 |

| Lady Jackson | Snagged and lost on the White River | October 14, 1863 |

| Hamilton Bell | Auxiliary vessel for Union navy | 1863–1864 |

| Celeste | Auxiliary vessel for Union navy | 1864 |

| Commercial | Auxiliary vessel for Union navy | 1864 |

| Dove | Auxiliary vessel for Union navy, involved in Action at Fitzhugh’s Woods, Affair at Kendal’s Grist Mill, and Expeditions from Helena to Harbert’s Plantation | 1864 |

| Kate Hart | Auxiliary vessel for Union navy | 1864 |

| Tom Sugg | Captured on the Little Red River by U.S. troops, later converted to gunboat USS Tensas | August 11, 1863, to 1865 |

| J. H. Miller | Auxiliary vessel for Union navy captured and destroyed by guerrillas | February 1864–August 17, 1864 |

| Leon | Snagged and lost at Barnum, Arkansas | March 1864 |

| Fanny Bullitt | Snagged and lost at Napoleon | March 15, 1864 |

| Homer | Captured by Union troops and scuttled at Camden (Ouachita County) | April 26, 1864 |

| I Go (Iago) | Captured by Confederates and burned on the Arkansas River | June 12, 1864 |

| Mariner | Burned above Helena | July 4, 1864 |

| John D. Perry | Auxiliary vessel for Union navy attacked by Confederates | September 9, 1864 |

| Marmora | Union transport attacked by Confederates | October 22, 1864 |

| Alamo | Auxiliary vessel for Union navy attacked by Confederates | November 29, 1864 |

| Mattie | Auxiliary vessel for Union used in Augusta Expedition | December 7–8, 1864 |

| Des Moines City | Snagged and lost on the Arkansas River | January 1865 |

| Diligent | Snagged and lost on the Mississippi River at Helena | January 10, 1865 |

| Ella | Auxiliary vessel used by Union navy in Augusta Expedition | January 4–27, 1865 |

| Belle of Peoria | Auxiliary vessel used by Union navy in Augusta Expedition and Expedition from Memphis to Southeastern Arkansas and Northeastern Louisiana | January–February 1865 |

| Ad. Hines | Auxiliary vessel used by Union forces attacked by Confederates at Ivey’s Ford | January 17, 1865 |

| Lotus | Auxiliary vessel used by Union forces attacked by Confederates at Ivey’s Ford | January 17, 1865 |

| Annie Jacobs | Auxiliary vessel used by Union forces attacked by Confederates at Ivey’s Ford | January 17, 1865 |

| New Chippewa (Chippewa) | Auxiliary vessel used by Union forces attacked by Confederates at Ivey’s Ford | January 17, 1865 |

| John Raine | Auxiliary vessel used by Union navy in Expedition from Memphis to Southeastern Arkansas and northeastern Louisiana | January–February 1865 |

| Autocrat | Auxiliary vessel used by Union navy in Expedition from Memphis to Southeastern Arkansas and Northeastern Louisiana | January–February 1865 |

| Laurel Hill | Auxiliary vessel used by Union navy in Expedition from Memphis to Southeastern Arkansas and Northeastern Louisiana | January–February 1865 |

| Fanny Ogden | Auxiliary vessel used by Union navy in Expedition from Memphis to Southeastern Arkansas and Northeastern Louisiana | January–February 1865 |

| Sallie List | Auxiliary vessel used by Union navy in Expedition from Memphis to Southeastern Arkansas and Northeastern Louisiana | January–February 1865 |

| Carrie Jacobs | Auxiliary vessel used by Union navy in Expedition from Memphis to Southeastern Arkansas and Northeastern Louisiana | January–February 1865 |

| Virginia Barton | Auxiliary vessel used by Union navy in Expedition from Memphis to Southeastern Arkansas and Northeastern Louisiana | January–February 1865 |

| Tycoon | Auxiliary vessel used by Union navy in Expedition from Memphis to Southeastern Arkansas and Northeastern Louisiana | January–February 1865 |

| Illinois | Auxiliary vessel used by Union navy in Expedition from Memphis to Southeastern Arkansas and Northeastern Louisiana | January–February 1865 |

| Ida May | Auxiliary vessel used by Union navy in Expedition from Memphis to Southeastern Arkansas and Northeastern Louisiana | January–February 1865 |

| Starlight | Auxiliary vessel used by Union navy in Expedition from Memphis to Southeastern Arkansas and Northeastern Louisiana | January–February 1865 |

| Maria Denning | Auxiliary vessel used by Union navy in Expedition from Memphis to Southeastern Arkansas and Northeastern Louisiana | January–February 1865 |

| Landes | Auxiliary vessel used by Union navy in Expedition from Memphis to Southeastern Arkansas and Northeastern Louisiana | January–February 1865 |

| Jim Barkman | Auxiliary vessel used by Confederate forces captured on Bayou Bartholomew and burned during Expedition from Memphis to Southeastern Arkansas and Northeastern Louisiana | January 31, 1865 |

| Curlew | Vessel used by Union forces for the Expedition from Helena to Friar’s Point, Mississippi, and the Scout from Helena to Clarke’s Store | February 1865 |

| Rose Hambleton |

Auxiliary vessel used by Union forces during the Scout from Little Rock to Bayou Meto and Little Bayou | May 6–11, 1865 |

| Progress | Snagged and lost on the Arkansas River | December 1865 |

| Rodolph | Snagged and lost on the Arkansas River 15 miles below Little Rock | December 1865 |

| Ella | Snagged and lost on the Arkansas River at Little Rock | December 13, 1865 |

| Progress | Burned and sank on the Arkansas River | January 2, 1866 |

| Catawba | Snagged and lost at Jacksonport (Jackson County) | February 7, 1866 |

| Market Boy | Foundered on the Mississippi River at Helena | May 25, 1866 |

| Kate Bruner | Snagged and sank at St. Charles | September 15, 1866 |

| Colossus | Snagged and sank at Pine Bluff | December 17, 1866 |

| Pilgrim | Snagged and sank on the Mississippi River 30 miles below Helena | December 6, 1867 |

| Florence Miller No. 2 | Burned and sank at Clarendon | December 23, 1867 |

| Judge Torrence | Snagged and lost at Ozark Island at Napoleon | February 19, 1868 |

| Centralia | Snagged and sank at Auburn Landing | May 27, 1868 |

| Florence Tabor | Snagged and lost on the Arkansas River | December 31, 1868 |

| Cherokee | Snagged and lost on the Arkansas River | 1869 |

| Leni Leoti | Snagged and lost on the Arkansas River | May 10, 1869 |

| Linton | Snagged and sank at the Arkansas River cutoff | October 25, 1869 |

| Van Buren | Snagged and lost above Pine Bluff | October 30, 1869 |

| Only Chance | Foundered at Douglas Landing | November 23, 1869 |

| Lizzie Gill | Foundered at Helena | January 10, 1870 |

| America | Snagged and sank on the Arkansas River | January 28, 1870 |

| Guidon | Snagged and sank on the Arkansas River | March 23, 1870 |

| Kenton | Snagged and lost at Helena | June 10, 1870 |

| Fairy Queen | Snagged on the Black River near Elgin (Jackson County) | July 9, 1870 |

| W. A. Caldwell | Sank in White River Cutoff | December 10, 1870 |

| Argos | Foundered on the White River at Batesville | July 27, 1871 |

| Virginia | Snagged and lost at Osceola (Mississippi County) | October 7, 1871 |

| Fort Smith | Snagged and sank on the White River | October 27, 1871 |

| Importer | Snagged and sank on the Arkansas River | January 15, 1872 |

| H. Clay Wilson | Snagged and sank at mouth of the White River | November 24, 1872 |

| Little Rock | Snagged and lost at Pine Bluff | December 1, 1872 |

| Webster | Lost to ice at Helena | December 28, 1872 |

| Hallie | Attacked in Battle of Palarm and later sank at Little Rock during the Brooks-Baxter War | 1874 |

| Belle of Texas | Used to transport troops for Battle of New Gascony during the Brooks-Baxter War | April 18, 1874 |

| Victor | Foundered at Pendleton (Desha County) | February 23, 1907 |

| C. E. Taylor | Foundered on the Black River | July 23, 1907 |

| City of Fulton | Burned and sank on the Red River at Fulton | October 8, 1907 |

| Chicago | Snagged and lost at Rob Roy (Jefferson County) | January 5, 1909 |

| Cora L. Roberts | Foundered at Big Rock on Arkansas River | October 15, 1914 |

| Washburn | Lost to ice at Crockett’s Bluff (Arkansas County) | January 12, 1918 |

| Alice | Burned and lost at Arkansas City | December 26, 1921 |

| Karlina | Burned and lost on the White River | April 10, 1933 |

For additional information:

“As Much as the Water: How Steamboats Shaped Arkansas.” Center for Arkansas History and Culture, University of Arkansas at Little Rock. https://ualrexhibits.org/steamboats/ (accessed January 7, 2022).

Baldwin, Leland Dewitt. The Keelboat Age on Western Waters. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1941.

Bates, Alan L. The Western Rivers Engine Room Encyclopoedium. Louisville, KY: Cyclopoedium Press, 1996.

———. The Western Rivers Steamboat Cyclopoedium, or, American Riverboat Structure and Detail, Salted with Lore. Leonia, NJ: Hustle Press, 1968.

Branam, Chris. “A Database of Steamboat Wrecks on the Arkansas River, Arkansas, Between 1830–1900.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2003.

Brown, Mattie. “A History of River Transportation in Arkansas from 1819–1880.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 1933.

Dethloff, Henry C. “Paddlewheels and Pioneers on Red River, 1815–1915, and the Reminiscences of Captain M. L. Scovell.” Louisiana Studies 6 (Summer 1967): 91–134.

Fitzjarrald, Sarah. “Steamboating the Arkansas.” Journal of the Forth Smith Historical Society 6 (September 1982): 2–30.

Gandy, Joan W., and Thomas H. Gandy. The Mississippi Steamboat Era in Historic Photographs: Natchez to New Orleans, 1870–1920. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1987.

Haites, Erik F., James Mak, and Gary M. Walton. Western Rivers Transportation: The Era of Early Internal Development, 1810–1860. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1975.

Hawkins, Van. Smoke up the River: Steamboats and the Arkansas Delta. Jonesboro, AR: Writers Bloc, 2016.

Huddleston, Duane, Sammie Rose, and Pat Wood. Steamboats and Ferries on White River: A Heritage Revisited. Conway: University of Central Arkansas Press, 1995.

Hunter, Louis C. Steamboats on the Western Rivers: An Economic and Technological History. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1949.

McCague, James. Flatboat Days on Frontier Rivers. Champaign, IL: Garrard Publishing Co., 1968.

Stewart-Abernathy, Leslie C. “Ghost Boats at West Memphis.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 67 (Winter 2008): 398–413.

Stewart-Abernathy, Leslie C., ed. Ghost Boats on the Mississippi: Discovering Our Working Past. Popular Series No. 4. Fayetteville: Arkansas Archeological Survey, 2002.

Way, Frederick, Jr. Way’s Packet Directory, 1848–1994. Rev. ed. Athens: Ohio University Press, 1994.

Way, Frederick, Jr., compiler, and Joseph W. Rutter. Way’s Steam Towboat Directory. Athens: Ohio University Press, 1990.

Leslie C. Stewart-Abernathy

Arkansas Archeological Survey

Battle of Palarm

Battle of Palarm  Choctaw Steamboat

Choctaw Steamboat  Choctaw Steamboat

Choctaw Steamboat  City of Camden Steamboat

City of Camden Steamboat  Clearing the Raft

Clearing the Raft  DeValls Bluff Steamboat

DeValls Bluff Steamboat  F. W. Tucker Steamboat

F. W. Tucker Steamboat  Fort Smith Drawing

Fort Smith Drawing  Frank R. Hill Steamboat

Frank R. Hill Steamboat  Handy Steamboat

Handy Steamboat  Hospital Steamer

Hospital Steamer  John Howard Steamboat

John Howard Steamboat  Judsonia Riverboat

Judsonia Riverboat  Kate Adams Steamboat

Kate Adams Steamboat  Mary Woods No. 2 Steamboat

Mary Woods No. 2 Steamboat  Steamboats

Steamboats  Steamboats Illustration

Steamboats Illustration  Sultana Disaster

Sultana Disaster  Sultana

Sultana  USS Queen City

USS Queen City  Welcome Steamboat

Welcome Steamboat

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.