calsfoundation@cals.org

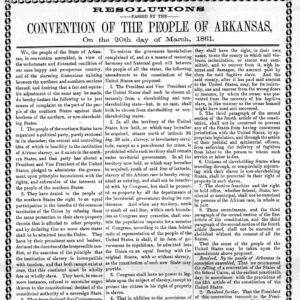

Secession Convention

On May 6, 1861, a body of men chosen by Arkansas voters in an election held on February 18, 1861, voted to remove Arkansas from the United States of America. Arkansas’s secession ultimately failed in 1865 due to the military defeat of the Confederacy.

States’ rights versus the national government had a contentious history prior to 1861. The Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions of 1798 and 1799 suggested that states retained powers to protect citizens from the federal government, and the Hartford Convention of 1814–1815 paved the way for the Doctrine of Nullification that South Carolina unsuccessfully invoked in 1832. States’ rights debates—notably among U.S. senators Daniel Webster, Robert Y. Hayne, and John C. Calhoun—led to a theoretical acceptance of this doctrine, but only by Southern Democrats.

In November 1860, the division within the Democratic Party between National Democrat Stephen A. Douglas and Southern Democrat John C. Breckinridge helped secure the election of Republican Abraham Lincoln. Although Lincoln would not be sworn into office until March 4, 1861, South Carolina passed an ordinance of secession on December 20, 1860. The Gulf states followed, and on February 8, 1861, a convention held at Montgomery, Alabama, adopted a provisional constitution for the Confederate States of America.

Arkansas voters were singularly uninformed on the contentious issues present in the 1860 presidential campaign, with upland counties, later Unionist strongholds, mostly giving heavy majorities to Breckinridge. Newly elected governor Henry Massie Rector in his inaugural address claimed that Lincoln’s victory had “revolutionized the government,” but whether he actually was calling for immediate secession was unclear.

By December, Rector was claiming that the Union no longer even existed, and former Whig leader Albert Pike had joined two Democrats, Senator Robert Ward Johnson and Congressman Thomas Carmichael Hindman, in calling for the summoning of a state convention to decide Arkansas’s role. The lower house passed a bill on December 22, but the state Senate did not act until January 16, 1861, by which time the Gulf states had joined South Carolina in seceding.

Before the voters could decide, Arkansas was the scene of a potentially explosive conflict. In early February 1861, as many as 1,000 armed men, most believing that Governor Rector had called for their assistance, descended upon Little Rock (Pulaski County) with the view of evicting the small caretaker force of sixty-five men at the U.S. Arsenal, commanded by Captain James Totten. Although bloodshed was avoided, the event galvanized outraged anti-secessionists who then organized for the upcoming election.

Under the law, voters decided whether or not to call a convention while simultaneously electing delegates should one be called. Although the summoning of a convention was approved 27,412 to 15,826, anti-immediate secession candidates won a majority of seats despite not even fielding candidates in three upland counties. The Arkansas Gazette analyzed the candidate returns and concluded that the vote was 23,626 for the Union and 17,927 for secession.

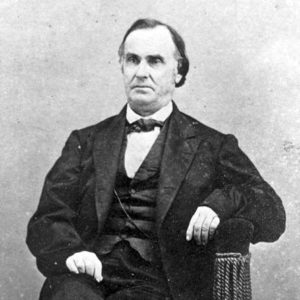

On March 4, 1861, coinciding with Lincoln’s inauguration, the convention assembled with Unionist Jesse Turner of Van Buren (Crawford County) as temporary chair. The next day, by a vote of 40–35, Unionist David Walker became the convention president. The Unionists held on to this majority throughout the first session.

Historian Ralph Wooster concluded that, compared to other states, the convention members for Arkansas were undistinguished, with no former governors, senators, or congressmen present. However, on the Unionist side, David Walker was one of the best-known politicians in the state, and able young Unionists included Augustus Hill Garland and William Meade Fishback.

The business of the convention was to decide whether or not to leave the Union. Rejecting pleas for an immediate vote, the convention settled in to debate the issues. Oratory was the order of the day. James Yell, a former Know-Nothing gubernatorial candidate, led the secessionist caucus, and Thomas B. Hanly (subsequently a Confederate congressman) was a leading secessionist spokesman. James Totten, the secessionist delegate from Arkansas County, advanced the view that Southerners, the descendants of the English cavaliers, could never co-exist with the Puritan Northerners. Another argument was economic. Williamson S. Oldham, a former Arkansas Democratic politician who had moved to Texas and represented the Confederacy, threatened Arkansas with economic boycott unless the state joined the movement. Other orators pictured a South whose slavery realm would eventually take in the entire Caribbean. Governor Rector thought the single issue was slavery—“They believe slavery is sin, and we do not, and there lies the trouble”—and the records of the first session reflect this, with each of the listed “causes of complaint on the part of the people of the southern states” being concerned with the preservation of slavery. Finally secessionist orators harped on Southern honor and manhood, and had a fine time denouncing Unionists as “submissionists,” a sexually loaded term.

Since the majority would not yield, some secessionists began urging the division of the state. To avoid what many considered a calamity, a compromise emerged. Secession would be referred to the voters in August; in the meantime, Arkansas would stay in the Union while working with other border states to settle the crisis. On March 21, 1861, the convention adjourned subject to the call of President David Walker.

Although debate continued around the state, it was the firing on Fort Sumter in South Carolina on April 12 that changed many minds. News stories slanted the facts in favor of the Confederacy. Then President Lincoln called on Governor Rector to supply 780 men to restore law and order and was promptly refused.

As pressure mounted, David Walker called the convention to assemble on the morning of May 6, 1861. Some Unionists still wanted a vote of the people, but that was rejected by a 55–15 margin. The ordinance for secession officially passed with only five opposing votes, but David Walker pleaded for the five to change their votes in order to make the decision unanimous. While four opposing delegates relented, Isaac Murphy, the delegate from Madison County, held out despite enormous pressure. Prominent Little Rock woman Martha Trapnall’s bouquet, thrown to the embattled delegate, indicated that no unanimity existed on this issue. Interestingly, the convention’s secretary, Elias Cornelius Boudinot, took no notice of Murphy’s action but noted that at ten minutes past four o’clock in the afternoon, Arkansas declared its independence from the United States of America. Admission to the Confederacy followed.

The work of the convention did not end with the passage of the ordinance. Governor Rector had long been seen as incompetent by both factions. “Oh Hell,” was the governor’s response on hearing that convention planned to unseat him. Instead, the convention created the Arkansas Army, appointed its officers, and gave the war power to a three-man commission. It then wrote an entirely new constitution that incorporated many Whig objectives, including legalizing banking. Since Rector had fought the convention at every step, it was not surprising that the constitution’s schedule for elections meant that Rector would not complete his four-year term. On June 3, 1861, the convention at last disbanded.

The Secession Convention’s two-fold roles in passing an ordinance of secession and in trying to put Arkansas on a war footing set the stage for the next five years. In the Ozarks and Ouachitas, many rejected secession, especially once the Confederacy initiated drafting men into the army. Governor Rector, although wounded, remained in power, and his subsequent actions, which included a threat to have Arkansas secede from secession, did not further the Confederate cause. Finally, four future Arkansas governors—Harris Flanagin, Isaac Murphy, Augustus Garland, and William Fishback—emerged as statewide figures from the convention, while David Walker not only returned to the Supreme Court of Arkansas but also served as chief justice.

For additional information:

Christ, Mark. K., ed. The Die is Cast: Arkansas Goes to War, 1861. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2010.

Dougan, Michael B. Confederate Arkansas: The People and Policies of a Frontier State in Wartime. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1976.

Gigantino, James J. II, ed. Slavery and Secession in Arkansas: A Documentary History. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2015.

Journal of Both Sessions of the Convention of the State of Arkansas, Which was Begun and Held in the Capitol, in the City of Little Rock. Little Rock: Johnson & Yerkes, State Printers, 1861.

Ross, Margaret. Arkansas Gazette: The Early Years, 1819–1866. Little Rock: Arkansas Gazette Foundation, 1969.

Woods, James M. Rebellion and Realignment; Arkansas’s Road to Secession. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1987.

Wooster, Ralph. “The Arkansas Secession Convention.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 13 (Autumn 1954): 172–195.

Michael B. Dougan

Jonesboro, Arkansas

Arkansas State Troops (CS)

Arkansas State Troops (CS) Bradley, Thomas H.

Bradley, Thomas H. Civil War Timeline

Civil War Timeline Politics and Government

Politics and Government Elias Boudinot

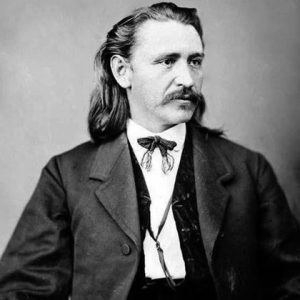

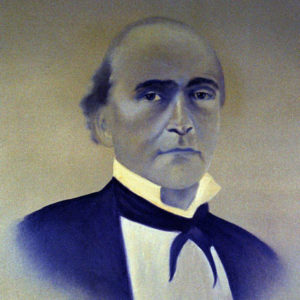

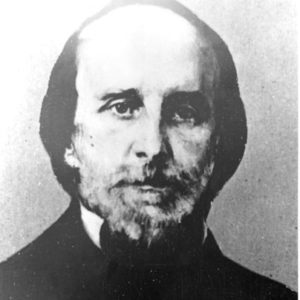

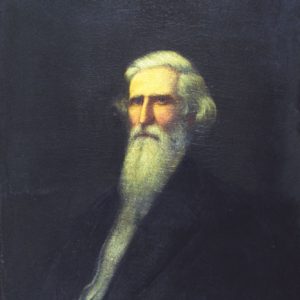

Elias Boudinot  William Fishback

William Fishback  Harris Flanagin

Harris Flanagin  Augustus Garland

Augustus Garland  Isaac Murphy

Isaac Murphy  Albert Pike

Albert Pike  Henry Rector

Henry Rector  Slavery Resolution

Slavery Resolution  David Walker

David Walker

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.