calsfoundation@cals.org

Hot Spring County

| Region: | Southwest |

| County seat: | Malvern |

| Established: | November 2, 1829 |

| Parent county: | Clark |

| Population: | 33,040 (2020 Census) |

| Area: | 614.94 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Historical population as per the U.S. Census: | |||||||||

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

458 |

1,907 |

3,609 |

5,635 |

5,877 |

7,775 |

11,603 |

12,748 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

15,022 |

17,784 |

18,105 |

18,916 |

22,181 |

21,893 |

21,963 |

26,819 |

26,115 |

30,353 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

32,923 |

33,040 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Population Characteristics as per the 2020 U.S. Census: | ||

| White | 26,525 | 80.3% |

| African American | 3,472 | 10.5% |

| American Indian | 189 | 0.6% |

| Asian | 114 | 0.3% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 11 | 0.0% |

| Some Other Race | 659 | 2.0% |

| Two or More Races | 2,070 | 6.3% |

| Hispanic Origin (may be of any race) | 1,265 | 3.8% |

| Population Density | 53.7 people per square mile | |

| Median Household Income (2019) | $43,889 | |

| Per Capita Income (2015–2019) | $21,866 | |

| Percent of Population below Poverty Line (2019) | 18.0% | |

Hot Spring County was established by an act of the territorial legislature in 1829 with land taken from Clark County. Located southeast of the Ouachita National Forest, Hot Spring County is bisected by the Ouachita River and includes landforms ranging from mountains to lowlands once covered in hardwood and pine forests. The combination of rock types and fault lines is responsible for the hot spring that provides the name for the county. This county, located in the southwest region of the state, has a diverse economy based on timber, manufacturing, mining, and agriculture (corn, cotton, and some rice).

Ironically, the spring for which Hot Spring County is named is no longer within the county limits. Garland County was created in April 1873 in response to complaints from the citizens of the city of Hot Springs about the difficult trip to the county seat, which was then Rockport. As a result, both the city of Hot Springs and the springs themselves (except for one near Magnet Cove) are no longer found in Hot Spring County.

The county’s mineral resources include iron, novaculite, titanium, barite, clay, and lignite. Magnet Cove got its name from the magnetic-iron-ore deposits that sent compasses spinning in the 1880s. There are forty-two distinct mineral species and mineral combinations in Magnet Cove, some of which are found only in Magnet Cove, the Ural Mountains, and the Tyrolean Alps.

The spring at Magnet Cove is set on the eastern edge of a series of outcroppings of novaculite that act like a sponge, soaking rainwater deep into the earth. Along the path of slow percolation, the water is enriched—and heated—by dissolved minerals in the rocks. After the water encounters the faults deep within the earth, it emerges quickly to the surface, maintaining much of its stored heat. The novaculite of the area has provided a major source for knife-sharpening whetstones and was mined from the 1880s to the 1970s.

Pre-European Exploration through European Exploration and Settlement

The Caddo tribe lived in this area until around AD 1700. They grew crops as well as gathering wild plants and other resources. Deposits of novaculite found in the Magnet Cove area were a source of material for weapons and tools, and trade distributed such items as far away as northern Louisiana and western Mississippi. Several archaeological sites in the county contain evidence of quarrying and tool manufacturing by people from different periods over thousands of years.

After the death of Hernando de Soto, members of his party crossed likely through Hot Spring County attempting to find a land route to Mexico. Historical markers erected in the twentieth century claim that de Soto’s party crossed the Ouachita River near contemporary Rockport, although such claims cannot be verified with certainty. Beginning in 1673, many French explorers visited the area, and a number of creeks that empty into the Ouachita River in Hot Spring County still bear the French names given to them at that time.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

In 1804, President Thomas Jefferson commissioned a planter and chemist, William Dunbar, and his associate, George Hunter, to explore along the Ouachita River. The goal of the Hunter-Dunbar Expedition was to explore and map the Ouachita River, noting the flora and fauna and the farming possibilities along the river.

The expedition party, traveling upstream, left a boat in the area that is now Rockport and traveled in smaller craft up the river as far as the mouth of Gulpha Creek. They were trapped there for an extended period over Christmas because the river had fallen too far for even their smaller boats to float downstream. Consequently, they camped on the river bank until the river rose enough for them to make their way back to Rockport.

In 1818, the Quapaw tribe ceded control of the lands surrounding the forty-three hot springs to the United States. However, the roads during this time were not developing at a rapid rate, and most of the smaller roads were impassable. The state’s first regular stagecoach service was established late in its territorial period and included the valuable connection between the state capital in Little Rock (Pulaski County) and the hot springs. The distance from Hot Springs to Little Rock took nineteen hours to cover by stage service.

Hot Spring County was formed from Clark County on November 2, 1829, becoming Arkansas’s eighteenth county. Hot Springs was named the county seat, which it remained until the county seat was moved to Rockport in 1846. Around that time, the first documented toll bridge in Arkansas was built where the Military Road crossed the Ouachita River at Rockport. It washed out in 1848.

This region was an important cotton-growing area, including land worked by enslaved people. An early incidence of racial violence took place in the county in 1836. An enslaved man only known as William was killed for allegedly attempting to escape bondage and resist his captors. Some of the first businesses were saloons and dry-goods stores. Saloons were populated by the local timber workers and were the sites of rowdy behavior.

Civil War through Reconstruction

Many young men of Hot Spring County fought in the Civil War, some for the Union army but more for the Confederacy. The Hot Spring County Hornets were one of the first groups organized in the county to battle for the Confederacy. Although no major Civil War battles were fought within the county, a significant skirmish did take place at Rockport on March 25, 1864.

Hot Springs thrived after the Civil War, unlike many other Arkansas towns. After six years of construction, a two-story county courthouse was completed in 1866, but it was destroyed by fire on January 23, 1873. Because the residents of the booming town were opposed to making the day-long trip over rough terrain to get to the county seat, they appealed to the state legislature to divide the county. On April 5, 1873, Hot Spring County was divided into Garland, and Hot Spring counties, with the original county retaining only the southern portion of its previous area. Rockport remained the seat for Hot Spring County. Hot Spring County was left with a single natural spring, in the Magnet Cove area.

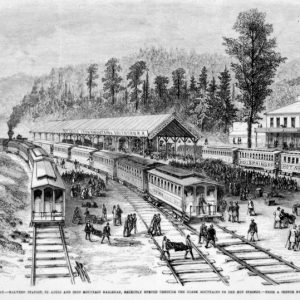

River transportation was becoming less important as the railroad moved west. The people of Rockport were asked if they would pay bonds to ensure that the rail would be placed within nine miles of the county seat. After Rockport declined the invitation, the Cairo and Fulton Railroad—later known as the Missouri Pacific Railroad—chose a more convenient route and laid out the town of Malvern in 1873. In the 1870s, Malvern served as a transfer point between the trains and the stagecoach routes.

Arkansas’s scenic mountains and hot springs with reportedly curative powers had attracted tourists since before the Civil War. After the war, many tourists were wealthy Northerners traveling to Hot Springs. Stagecoach robberies were reportedly frequent. The growth of the railroad system provided great opportunities for economic growth and prosperity, especially boosting the tourism industry. Hot Springs connected to Malvern via the main line of the Iron Mountain Railroad in 1875.

Post Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

The impact of the railroad was felt immediately in many ways, including within the timber industry. Because of the wet conditions, trees grew quickly. Malvern Lumber, established in 1880, was the first of several companies to make use of the trees of Hot Spring County. Unlike many of its competitors, Malvern Lumber practiced timber conservation measures, including limited logging and planting of new trees. The cheap land and cheap labor of Arkansas was appealing for purchase and development by Northern landowners. Ferry and steamboat travel had moved people and goods along the Ouachita River.

The popularity of river travel yielded to the efficiency of rail, and on October 15, 1879, fast-growing Malvern officially replaced neighboring Rockport as the county seat. A two-story brick courthouse was built ten years later, in 1888, drawing upon one of the new local industries, brick-making. With plants in Malvern and Perla, Atchison Brick Company—later known as Arkansas Brick and Tile—has continued to produce bricks for local, national, and international use. The Arlington Hotel in Hot Springs was built from brick made in the Perla plant. Arkansas Brick and Tile was acquired by Acme Brick Company of Fort Worth, Texas, in 1927.

Early Twentieth Century

On December 17, 1914, Malvern and Arkadelphia (Clark County) began to receive the benefits of electricity. Various electric companies had tried and failed to deliver reliable electric service to larger areas. Harvey Crowley Couch’s Arkansas Power and Light (AP&L) built the state’s first electric transmission line, which extended over the twenty-two miles between Arkadelphia and Malvern. His company later built the Remmel and Carpenter hydroelectric dams on the Ouachita River, creating Lake Hamilton and Lake Catherine, the latter of which is now a state park in the county.

In 1921, the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) made its presence known in Malvern when it made donations to local Christmas funds. The revival of this racist and violent organization was rooted in concerns about the challenges posed by the changing of the social order, as well as in racism. While these concerns were not unique to Hot Spring County, the rhetoric of the KKK struck a chord with the residents of the county; at its peak in the 1920s, the Klan had more than 1,000 members in the county, including several ministers. Local newspapers reported frequently on Klan activities and even printed applications for membership in the Klan. John Henry Harrison, an African American man employed at a local lumber mill, was killed by a mob in 1922 for allegedly frightening white girls.

Early-century prosperity was bound up in the timber industry. Once considered inexhaustible, the supply of hardwoods had been severely reduced by World War I. Many large timber mills closed in the 1920s. Local industry turned its focus to the few marketable quantities of ores. Novaculite, vanadium, and magnetic ore all were found to have commercial uses, and companies formed to exploit other rare minerals available in the Magnet Cove area. Arkansite, a rare but commercially unsuccessful mineral, is also found in the county. Clem Bottling Works produced soft drinks in Malvern for more than a half century.

In 1936, at the cost of $150,000, the present three-story brick courthouse was constructed. The jail stood on the top floor, above the courtroom and offices. In 2009, however, the Hot Spring County Detention Center replaced that jail. The courthouse is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Hot Spring County Library was established in Malvern in 1928 by the Women’s Club of Malvern. During the years of the Depression, the library struggled to survive, as the Women’s Club made frequent appeals to the public for donations of money or books. Finally, in 1939 the city of Malvern voted a one-mill tax to support the library. Malvern’s city hall was built in 1930 using Works Progress Administration (WPA) labor.

On June 10, 1936, President Franklin Roosevelt drove up from Hot Springs to visit Hot Spring County. After lunch at Lake Catherine at the home of Harvey Couch, the president and his entourage attended a service at Rockport Methodist Church, took part in ceremonies in Rockport and in Malvern, and then boarded a train in Malvern to travel to Little Rock. Hot Spring County residents had spent months preparing for the visit (part of Arkansas’s centennial celebration) by improving private property, planting flowers and shrubs, and paving the highway from Hot Springs to Malvern.

World War II through the Modern Era

World War II brought an unprecedented demand for the barite found in Hot Spring County—the solid deposits of barite were useful in oil-well drilling. Following the war, various industries were established in the county, including Baroid Drilling Fluids (1950), Mid-State Construction and Materials (1962), and United Minerals Corporation (1994). Manufacturing concerns based on wood products also reemerged, including Malvern Wood Products (1951) and Anthony Timberlands (1969).

The Arkansas Louisiana Gas Company produced a small car in Malvern in the mid-1960s. Called the Handywagon, the vehicle was designed for use by company employees.

Hot Spring County is located along U.S. Highways 67 and 270 and on Interstate 30. It includes routes of the Arkansas Midland and Union Pacific railroads. The Malvern Municipal Airport handles the aircraft of small businesses. Other communities in the county include Donaldson, Friendship, Midway, Perla, DeRoche, Glen Rose, and Bismarck.

Education

Hot Spring County has five public school districts. Malvern is the home of Arkansas State University-Three Rivers, a two-year college focused on training skilled workers and providing a basis for further study at a four-year college.

Industry

The Acme Brick Company processes a great deal of the local mineral resources. The people of Malvern commemorate this tradition of industry with the annual summer festival of Brickfest, which began in 1981. Several businesses also process the large stores of sand and gravel found in the county.

The timber industry continues to thrive in the great deal of land owned by large companies, including Deltic Timberland and Georgia Pacific. In 2002, an Arkansas state prison was established outside of Malvern, which has provided more jobs in the area.

Attractions

Two of the region’s five “diamond lakes” provide a wonderful opportunity for rest and recreation. DeGray Lake Resort State Park straddles Clark and Hot Spring counties. It is Arkansas’s only resort state park and is a favorite for water sports, camping, and golf. Lake Catherine State Park lies along the northern boundary and is a favorite for fishing and boating. Rock collectors are attracted to mineral collecting at Magnet Cove. The Rockport Ledge section of the Ouachita River in Hot Spring County has become increasingly popular with paddling and whitewater enthusiasts. The Ouachita streambed salamander is a species found only in a small area in the county near Lake Catherine.

For additional information:

Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Central Arkansas. Chicago: Goodspeed Publishing Company, 1889.

The Heritage. Malvern, AR: Hot Spring County, Arkansas, Historical Society (1970–).

Hot Spring County Chamber of Commerce. http://www.malvernchamber.com (accessed February 28, 2021).

Massay, Elizabeth Doffie. A Pictorial History of Malvern and Hot Spring County. Malvern, AR: 1990.

Jennifer Atkins-Gordeeva

Maumelle, Arkansas

Staff of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Revised 2022, David Sesser, Henderson State University

Antioch (Hot Spring County)

Antioch (Hot Spring County) Beaton (Hot Spring County)

Beaton (Hot Spring County) Bismarck (Hot Spring County)

Bismarck (Hot Spring County) Bonnerdale (Hot Spring County)

Bonnerdale (Hot Spring County) Butterfield (Hot Spring County)

Butterfield (Hot Spring County) Caney (Hot Spring County)

Caney (Hot Spring County) Central (Hot Spring County)

Central (Hot Spring County) Cross Roads (Hot Spring County)

Cross Roads (Hot Spring County) DeRoche (Hot Spring County)

DeRoche (Hot Spring County) Donaldson (Hot Spring County)

Donaldson (Hot Spring County) Ebenezer (Hot Spring County)

Ebenezer (Hot Spring County) Friendship (Hot Spring County)

Friendship (Hot Spring County) Glen Rose (Hot Spring County)

Glen Rose (Hot Spring County) Harp (Hot Spring County)

Harp (Hot Spring County) Hot Spring County Historical Society

Hot Spring County Historical Society Hot Spring County Museum

Hot Spring County Museum Jones Mills (Hot Spring County)

Jones Mills (Hot Spring County) Lono (Hot Spring County)

Lono (Hot Spring County) Magnet Cove (Hot Spring County)

Magnet Cove (Hot Spring County) Malvern-Hot Spring County Library

Malvern-Hot Spring County Library Midway (Hot Spring County)

Midway (Hot Spring County) Mount Moriah (Hot Spring County)

Mount Moriah (Hot Spring County) Overton, William Ray

Overton, William Ray Point Cedar (Hot Spring County)

Point Cedar (Hot Spring County) Rolla (Hot Spring County)

Rolla (Hot Spring County) Saginaw (Hot Spring County)

Saginaw (Hot Spring County) Social Hill (Hot Spring County)

Social Hill (Hot Spring County) Baker's Cafe

Baker's Cafe  DeGray Lake Resort State Park

DeGray Lake Resort State Park  Estep Cemetery

Estep Cemetery  Hot Spring County Courthouse

Hot Spring County Courthouse  Hot Spring County Map

Hot Spring County Map  Kimzeyite

Kimzeyite  Lake Catherine State Park

Lake Catherine State Park  Malvern Railroad Station

Malvern Railroad Station  Ouachita Technical College

Ouachita Technical College  Perla

Perla

When I was a kid, Grandpa (Sam) Bollen told me that there were a few slave owners in Friendship (Hot Spring County) at one time, and some of the huge drainage ditches in the Ouachita River bottomland were dug by slave labor. One in particular was the drainage ditch in the middle of the “Lee Bollen field.” He went on to tell that the slave-owners were not always cruel to their slaves. Grandpa said that each Christmas, the slave owners would tell their male slaves to go out and cut him a backlog apiece for his fireplaces, and the number of days it lasted in the fireplace was how many days the slave got off for Christmas to spend with his family or do whatever he pleased. The slaves would go and cut the biggest butt-cut of a hardwood tree they could find, tie it off out in the Ouachita River, and let it soak for at least a week. That waterlogged stick of wood would burn for at least for three to four days, and that is how long the slaves got off for Christmas.