calsfoundation@cals.org

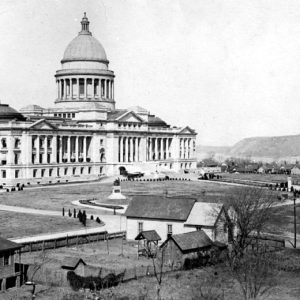

Desegregation of the Arkansas State Capitol

In 1964, Ozell Sutton, an African American man, sought to exercise his right to eat at the Arkansas State Capitol cafeteria. Initially turned away, he later successfully sued in the courts for service without discrimination. The state’s attempt to privatize the cafeteria and thereby avoid desegregation was ruled unlawful. Nonviolent direct action demonstrations by students and a petition from local white clergy helped to speed the case through the courts.

On July 15, 1964, Sutton attempted to eat a meal in the Arkansas State Capitol cafeteria in the basement of the building. The Civil Rights Act of 1964, which required the desegregation of public accommodations, had become national law just two weeks earlier. However, Sutton was refused service. On July 21, the capitol cafeteria was incorporated as the private, nonprofit Capitol Club.

Businesses across the South at the time sought to reinvent themselves as private clubs in hopes of evading the strictures of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. However, in the cases of Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United States and Katzenbach v. McClung—both decided by the U.S. Supreme Court in December 1964—the Court upheld the act’s contention that the U.S. Constitution’s commerce clause forbade racial discrimination even in privately run businesses.

In fact, the case of the Capitol cafeteria was even more straightforward than the other two cases. The Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause, which forbids government from engaging in racial discrimination but was understood not to cover private businesses, already covered the cafeteria. The courts had previously upheld that businesses operating in conjunction with state entities could not discriminate against Black customers. On this basis, Sutton had the right to eat at the capitol cafeteria even before the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. On September 16, Sutton, backed by National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) attorneys, filed a class-action suit against the Capitol Club in the U.S. District Court.

On March 11, 1965, at around 11:45 a.m., a group of thirty-two people made up of Philander Smith College students and Arkansas Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) project volunteers tried to eat at the Capitol Club. When the students were refused service, they stood their ground. Then, according to SNCC volunteer Arlene Wilgoren, an attack took place in which “approximately 15 or 20 [state] troopers pushed, shoved, kicked, hit, slapped and threw bodies down the hall.”

The students met SNCC volunteer Bill Hansen along with another group of students outside. They re-entered the capitol, and Hansen, along with another white SNCC volunteer, Nancy Stoller, led the combined group toward the stairwell. State troopers at the top of the stairs restrained most of the students. Ten made it past them into the basement where yet more state troopers confronted them. Hansen, Stoller, and the others were pushed back up the stairs. Later that day, approximately 200 SNCC volunteers and college and high school students marched on the capitol, only to have their entrance blocked by state troopers.

On March 18, at 1:00 p.m., Jim Jones, Arkansas SNCC project director; the Reverend Ben Grinage, Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) SNCC project director; and Anthony Hines, a Philander Smith student, led a group of fifteen people to the Capitol Club. After another failed attempt to use the facility, the state police charged at them. The next day saw similar scenes. This time, bystanders also attacked the demonstrators. One hurled a bottle of mustard gas at them. The volatile and highly corrosive liquid, used as a chemical weapon in World War I, quickly created noxious fumes. A number of people were hospitalized.

On March 22, a group of forty-nine ministers led by white Episcopal bishop the Reverend Robert R. Brown marched on the state capitol. Clarence Thornbrough, Governor Orval Faubus’s executive secretary, was there to receive them. Brown told Thornbrough, “We respectfully petition the governor to consider the aspects of closing the cafeteria. And we ask him to reopen the cafeteria to all sorts and conditions of people.”

The student and ministerial protests had the intended effect of oiling the wheels of justice. The same day that the ministers arrived at the capitol with their petition, Judge J. Smith Henley wrote to Sutton’s and the Capitol Club’s attorneys to set a trial date. On April 12, 1965, Henley handed down his decision in the case, ruling that the discrimination against Sutton was a straightforward breach of the Fourteenth Amendment mandate against government denying equal protection under the law. He ordered the Capitol Club to integrate and the defendants to pay the costs of the lawsuit.

On April 29, Secretary of State Kelly Bryant announced that the cafeteria would reopen to the public the following morning at 7:00 a.m. The next day, Sutton returned alone to the cafeteria where he had been refused service ten months earlier. He joined the line, collected his food, and ate lunch without incident.

For additional information:

Carter, Vic. From Here to Yonder: The Life and Work of Dr. Ozell Sutton. N.p.: Lee-Com Media Services, 2008.

Cortner, Richard C. Civil Rights and Public Accommodations: The Heart of Atlanta and McClung Cases. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2001.

Kirk, John A. “Capitol Offenses: Desegregating the Seat of Arkansas Government, 1964–1965.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 72 (Summer 2013): 95–119.

———. “Showdown at the Cafeteria: It Took Protests and the Court to Make the Capitol Follow Law.” Arkansas Times, February 14, 2013, pp. 1, 14–18. Online at http://www.arktimes.com/arkansas/the-fight-to-desegregate-the-arkansas-capitol-cafeteria/Content?oid=2681828 (accessed October 13, 2021).

Wallach, Jennifer Jensen, and John A. Kirk, eds. Arsnick: The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2011.

John A. Kirk

University of Arkansas at Little Rock

Civil Rights Movement (Twentieth Century)

Civil Rights Movement (Twentieth Century) World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967

World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967 State Capitol Building

State Capitol Building  Ozell Sutton

Ozell Sutton

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.