calsfoundation@cals.org

Monroe County

| Region: | Southeast |

| County Seat: | Clarendon |

| Established: | November 2, 1829 |

| Parent Counties: | Arkansas, Phillips |

| Population: | 6,799 (2020 Census) |

| Area: | 607.47 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Historical Population as per the U.S. Census: | |||||||||

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

461 |

936 |

2,049 |

5,657 |

8,336 |

9,574 |

15,336 |

16,816 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

19,907 |

21,601 |

20,651 |

21,133 |

19,540 |

17,327 |

15,657 |

14,052 |

11,333 |

10,254 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8,149 |

6,799 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Population Characteristics as per the 2020 U.S. Census: | ||

| White |

3,568 |

52.5% |

| African American |

2,760 |

40.6% |

| American Indian |

35 |

0.5% |

| Asian |

28 |

0.4% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander |

7 |

0.1% |

| Some Other Race |

144 |

2.1% |

| Two or More Races |

257 |

3.8% |

| Hispanic Origin (may be of any race) |

186 |

2.7% |

| Population Density |

11.2 people per square mile |

|

| Median Household Income (2019) |

$38,468 |

|

| Per Capita Income (2015–2019) |

$23,538 |

|

| Percent of Population below Poverty Line (2019) |

27.1% |

|

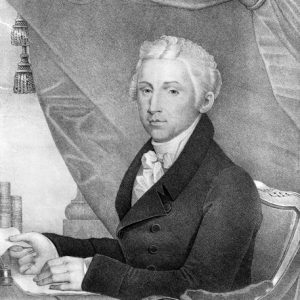

Monroe County, named for President James Monroe, is located approximately halfway between Little Rock (Pulaski County) and Memphis, Tennessee. Notable communities include Brinkley, Clarendon, Holly Grove, Indian Bay, Blackton, Fargo, and Roe.

Monroe County is adjacent to Arkansas, Prairie, and Woodruff counties. The White River separates Monroe and Arkansas counties, while the Cache River separates Monroe and Prairie counties. The county’s economic base is farming, and the land is among some of the most fertile in the state. About 1,500 acres in the county’s southeastern corner are protected by levee, but much of the remainder is subject to flooding. The area is drained by the White and Cache rivers, DeView and Roc Roe bayous, and several sloughs and creeks.

Pre-European Exploration

Near Indian Bay, in the south end of the county, nine Native American mounds have been found, with the largest covering about one and a half acres. Several of the mounds measured three to four feet high and thirty feet in circumference. Various archaeologists have attributed these and other mounds found in the county, in addition to collected artifacts, to various Native American groups including the Quapaw, the Plum Bayou Culture, and the Hopewell Culture. Indian artifacts have been located at various points around the county.

European Exploration and Settlement

Europeans had already arrived in what became Monroe County by 1799 when Antoine Tessier and Joseph de Plasse, thought to be French hunters and trappers, were living at the mouth of the Cache River, which later became Clarendon. When the first settlers arrived, virgin forest covered most of the area, although there were small, cleared patches where Indians grew crops such as corn, beans, and squash. Area trees included beech, black oak, ash, sweet gum, water tupelo, and bald cypress. Turkeys, ruffled grouse, woodpeckers, squirrels, deer, geese, ducks, bears, and muskrats were common. Most early settlers arrived via the White River.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

Beginning in October 1815, federal surveyors Prospect Robbins and Joseph Brown came to Arkansas to begin the survey of the Louisiana Purchase by establishing the initial survey point or base line. Following their orders, Brown and Robbins established the point in a swamp about eight miles east of the present location of Clarendon. In 1824, Congress authorized the construction of an all-weather military road to connect Memphis with Little Rock. When completed in 1828, the road entered Monroe County from the northeast, crossed the White River near the mouth of the Cache River, and exited to the southwest, thus allowing easier overland passage for settlers to come to the county. The road made use of a ferry to cross the White River where Sylvanus Phillips had established the earliest known ferry in 1827. When the county was formed, the house of Ester Maddox in Lawrenceville became the temporary county courthouse. Maddox’s late husband, Thomas Maddox, had offered his home to the Arkansas General Assembly for the purpose while they debated formation of the county. Commissioners later placed a permanent county courthouse on the farm of Joseph Jacobs. The first actual courthouse was erected at Lawrenceville in 1846. The county seat was then moved to Clarendon in 1857. The current courthouse, designed in Italian Renaissance Revival style, was constructed in 1911 and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1976.

Civil War through Reconstruction

In 1860, there were 2,226 slaves in Monroe County with 3,431 white residents. At the 1861 Secession Convention, William Mayo represented the county. He owned at least fifty-four enslaved people at the time of the 1860 federal census. Since growing cotton using slave labor and sending it to market down the White River was a major enterprise in the county, white residents favored the Confederacy in the Civil War, and at least seven companies of soldiers were raised. Use of the White River was imperative to both sides, since troops and goods could be moved by water to DeValls Bluff (Prairie County) and by railroad to Little Rock. In addition, the Military Road crossed the county. These factors led to many military actions in the county during the war.

One of the most important events began when a flotilla of at least six Union gunboats moved up the White River from June 10, 1862, to July 15, 1862. A group of citizens met the squadron when it reached Clarendon and told the naval leader that the townspeople were not involved in the war. After the commander warned the citizens that the city would be destroyed if they fired on the gunboats, the flotilla moved on upriver. A skirmish was fought at Cache Bayou on July 15. Clarendon was captured again by Federal forces the following month. Federal troops crossed the county in the summer of 1863 during the Little Rock Campaign, leading to the Skirmish at Harrison’s Landing.

The USS Queen City, a Federal gunboat anchored in the White River there, was attacked and sunk by Confederate forces under General Joseph Shelby on June 24, 1864. The following day, Federal troops arrived from DeValls Bluff. First they attacked Shelby’s forces, driving them away, and then they burned most of Clarendon. Other engagements and actions in the county included the Skirmish at Lawrenceville and an expedition to Clarendon. Confederate forces attacked other Union boats on the White River, including the steamer Perry and tug Resolute, but none were as consequential as the attack on the Queen City.

After the war, animosity toward the Union remained, as was illustrated in the October 24, 1868, Arkansas Gazette reporting that James Hinds, a Republican U.S. congressman, and Joseph Brooks, a Republican candidate for the U.S. Senate, were attacked by “radicals” near Indian Bay. It was soon learned that Hinds was dead but that Brooks had survived.

John C. Palmer, former law partner of Thomas C. Hindman, began construction on an elaborate home in eastern Monroe County in 1870. The Italianate-style home, known as Palmer’s Folly, stood until it burned while being restored in 2013.

Post Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

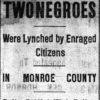

Numerous incidents of racial violence occurred in the county in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Lynched in 1887, Leach Magee had allegedly assaulted a white woman. A mass lynching took place in 1893, with five men killed for three alleged murders. Another mass lynching took place just five years later in 1898, with two men and two women being killed after allegedly plotting to kill a white man. Records indicate at least twenty people, both African American and white, were lynched in the county between 1876 and 1915.

In 1884, Simon Hughes, a Clarendon lawyer and former Arkansas attorney general, was elected governor and served two terms. The Consolidated White River Academy was established in 1893 in Brinkley with the goal of providing a good education to African Americans. Students from around Arkansas and the nation attended the boarding school until it closed in 1950.

From about 1870 to about 1930, the timber business became important for much of the county as lumber mills were established around the county. This continued until most of the county’s hardwood timber was decimated.

Early Twentieth Century

Two natural disasters between 1900 and 1930 devastated large sections of the county. First was a massive tornado on March 8, 1909, that destroyed everything in its path from about five miles southwest of Brinkley to about ten miles northeast of it. Thirty-five were dead, and around 200 were injured. Nearly every building in the city was destroyed or damaged. Second was the Flood of 1927 along the White River, which soon covered most settlements in the lower section of the county. On April 20, the levee system protecting Clarendon failed; soon, the town stood in twenty feet of water.

During World War I, Monroe County citizens joined others across the country in supporting the war effort by buying war bonds, planting victory gardens, and raising money for the Red Cross. In 1917, Clarendon citizens raised $237.89 for a silver service for the battleship Arkansas. Navy recruitment parties were held in Brinkley and Clarendon in early December 1917 to raise 1,000 men in the shortest time possible.

Conservation movements growing in the 1920s resulted in the formation of the Dale Bumpers White River National Wildlife Reserve during the 1930s. About 22,100 acres of Monroe County are included in the White River Refuge and the Sheffield Nelson Dagmar Wildlife Management Area. Part of the county is also included in the Cache River National Wildlife Refuge.

World War II through the Modern Era

During World War II, county citizens responded as they had during World War I. For instance, Farrell Locomotive Machine Shop was converted to produce goods for the Department of War. In January 1942, it was learned that county native Pearl McCain, a Methodist missionary to China, was being held hostage by the Japanese. McCain survived the war and continued to serve in China until the communist takeover led her to return to Japan.

From World War II to the present, the county has remained an agricultural area, although farming has become increasingly more mechanized. The main crops are cotton, corn, soybeans, and rice.

County schools began following the “freedom of choice plan” for minority students by the mid-1960s. By the 1970–1971 school year, the schools were desegregated. By the early twenty-first century, consolidation had led to only two districts operating in the county: Clarendon and Brinkley.

There are several points of interest in the county. The Fargo Agricultural Museum commemorates the work of Dr. Floyd Brown, who began the Fargo Agricultural School, an institution for Black students patterned after Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. The well-kept home place of writer Margaret Moore Jacobs is in Clarendon. Central Delta Depot Museum in Brinkley has a bust of local jazz and blues performer Louis Jordan, and off Highway 49, about fifteen miles south of Brinkley, is the Louisiana Purchase Historic State Park. The Great Southern Hotel and the Ellis and Charlotte Williamson House are located in Brinkley.

For additional information:

Central Delta Historical Journal. Brinkley, AR: Central Delta Historical Society (1997–).

English, Jo Claire. Pages from the Past Revisited: Historical Notes on Clarendon, Monroe County and Arkansas. Clarendon, AR: J. C. English, 1991.

Maxwell, George R., Cornelius Harris, and Warren A. Gore. Soil Survey of Monroe County, Arkansas. Washington DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture Soil Conservation Service, 1978.

Louise Mitchell

Central Delta Historical Society

Revised 2022, David Sesser, Southeastern Louisiana University

Grand Prairie, Skirmish at

Grand Prairie, Skirmish at Monroe County Lynching of 1893

Monroe County Lynching of 1893 Monroe County Lynching of 1915

Monroe County Lynching of 1915 Ricks, G. W. and Moses (Lynching of)

Ricks, G. W. and Moses (Lynching of) Blackton School

Blackton School  Blackton Street Scene

Blackton Street Scene  Brinkley Cyclone Damage

Brinkley Cyclone Damage  Central Delta Depot Museum

Central Delta Depot Museum  Clarendon Button Factory

Clarendon Button Factory  Fargo Agricultural School

Fargo Agricultural School  Louisiana Purchase Historic State Park Marker

Louisiana Purchase Historic State Park Marker  Monroe County Courthouse

Monroe County Courthouse  Monroe County Map

Monroe County Map  James Monroe

James Monroe

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.