calsfoundation@cals.org

Rogers (Benton County)

| Latitude and Longitude: | 36º19’55″N 094º07’06″W |

| Elevation: | 1371 feet |

| Area: | 38.89 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 69,908 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | June 6, 1881 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

1,265 |

2,158 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

2,820 |

3,318 |

3,554 |

3,550 |

4,962 |

5,700 |

11,050 |

17,429 |

24,692 |

38,829 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

55,964 |

69,908 |

|

Rogers was founded as a stop on the St. Louis–San Francisco Railway (Frisco) and developed as a shipping point for apples and a trade center for the surrounding rural area. After World War II, agriculture remained important, but business leaders also embarked on a successful effort to recruit light industry. Rogers has several major industrial plants and retail centers and is one of the fastest-growing cities in Arkansas.

Louisiana Purchase through Reconstruction

Settlers began to arrive in the vicinity of what is today Rogers around 1830. Most came from the Upper South states, especially Tennessee. The foundation of the local economy in the mid-1800s was subsistence farming, with tobacco as the main cash crop. The many streams in the region provided power for grist and lumber mills, and abundant timber allowed early industrialist Peter Van Winkle to establish a lumber empire near the hamlet of War Eagle (Benton County), east of what is today Rogers.

A major state road ran through what is now the city of Rogers. This road was part of the route used by the Butterfield’s Overland Mail Company organized in 1857 by John Butterfield to carry the United States mail from Tipton, Missouri, to California. Callahan’s Tavern, a stagecoach inn near a large spring in what is now northeastern Rogers, was a stop on the Butterfield route. The Butterfield Overland Mail route was discontinued after the outbreak of the Civil War because it ran through Confederate territory.

The Civil War put local residents in the crossfire between Union and Confederate armies. There were major military camps within a few miles of the center of town, and in March 1862, the Battle of Pea Ridge took place nearby. Many barns, mills, and homes in the area were destroyed, and the economic and social development of the region was devastated.

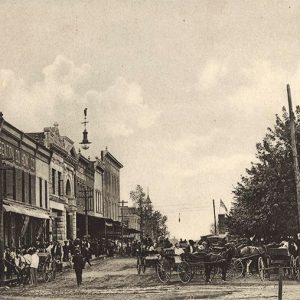

Residents devoted the 1870s to rebuilding. The 1880s saw the arrival of rail transportation. The Frisco followed a route through eastern Benton County, bypassing the county seat of Bentonville (Benton County). The railroad established stations along the route, and around each of those stations, a town sprang up. One of those towns was Rogers.

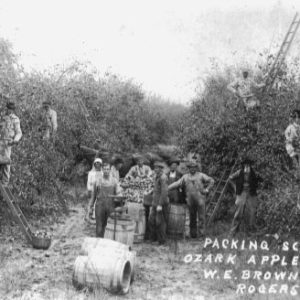

Rogers celebrates May 10, 1881, as its birthday, the day the first train pulled into town to be greeted by an enthusiastic crowd. The town with an estimated population at incorporation of 600 people was named for Captain Charles Warrington Rogers, general manager of the Frisco. The railroad advertised the Rogers area across the Midwest, and as newcomers from states such as Iowa and Illinois arrived, Rogers began to grow. The town owed its growth to the fact that it was both a local trade center and a major shipping point for apples and apple products.

Post-Reconstruction through Early Twentieth Century

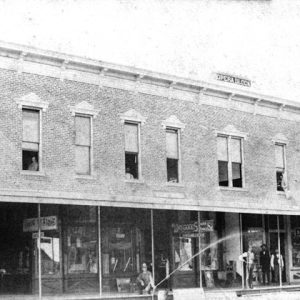

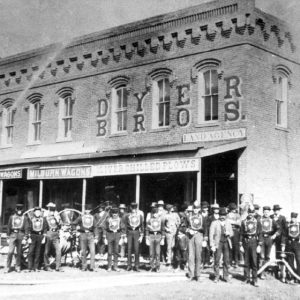

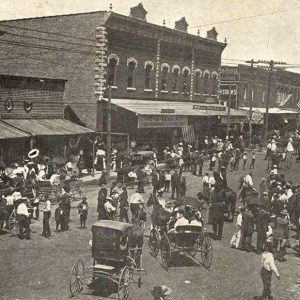

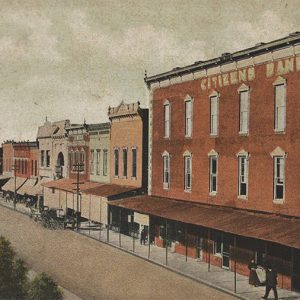

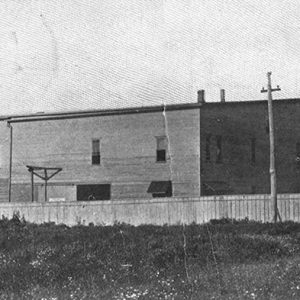

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, orchards surrounded Rogers. Along the railroad tracks were produce houses, apple evaporators where apples were sliced and dried, and an enormous apple cider vinegar plant. By the early 1900s, Rogers boasted a brick commercial district, concrete sidewalks, an electric light plant, public schools and a private academy, and an opera house. The light plant and school building are gone, but the opera house and most of the other early brick commercial buildings are still standing today.

As early as 1907 and as late as 1980, the printed record boasted of Rogers’s status as a sundown town, or a community where African Americans were not allowed to live.

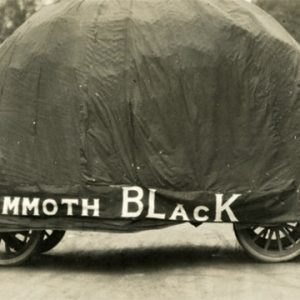

By the 1920s, Rogers had grown to over 3,000 residents. The Apple Blossom Festivals, held each spring from 1924 through 1927, attracted thousands of people to Rogers to see the floats, tour the orchards in bloom, and see the Apple Blossom Queen crowned. However, bad weather often plagued the events. The apple industry itself also was in decline since disease and insects had begun to wreak havoc in the orchards. The festival ended, and soon poultry replaced apples as the main agricultural product.

Population growth in Rogers slowed dramatically during the Great Depression. All but one of the community’s banks failed. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) offered employment to jobless residents and completed a number of local projects, including the building of Lake Atalanta. The lake became the centerpiece of a large city park still serving the community today. The Rogers Relief Association raised funds for the needy, and entertainer Will Rogers, whose wife was from the town, gave a benefit performance to help the relief effort.

World War II through the Modern Era

Late in 1940, Rogers’s National Guard unit, Battery F of the 142nd Field Artillery, was mobilized to active duty in anticipation of the outbreak of war. After World War II began, other Rogers men and women joined members of that unit in the military. Locally, the Red Cross made surgical bandages and knitted gloves, sweaters, and helmet liners. Schoolchildren participated in War Bond drives and collected scrap metal. Many residents left Rogers to work in defense plants, and some never returned. City leaders saw the need to attract industry to Rogers and began to work toward that goal.

Likely in an attempt to increase tourism to the area, the Ozark Golden Wedding Jubilee, a large celebration of couples who had been married fifty years, was held in 1949 and again in 1950 but did not continue further.

After World War II, homegrown industries expanded, and companies from elsewhere opened plants. Among the first to relocate was Daisy Manufacturing, a maker of air guns that moved its entire operation to Rogers from Plymouth, Michigan, in 1958. During the next four decades, the poultry industry expanded, and new industrial plants opened. The construction of Beaver Dam, begun in 1960, created Beaver Lake, providing recreation for tourists and retirees and assuring a water supply for industry. The resulting growth brought increased ethnic diversity to what had been a largely white, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant community, and by 2010, thirty-one percent of the population of Rogers was Latino. Longtime mayor Steve Womack sought to earn political capital from his denunciations of immigration, being elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 2010 as part of the Tea Party movement.

Education, Industry, Attractions, and Famous Residents

During its early years, Rogers was served by both public schools and the private Rogers Academy. By 2011, the Rogers Public Schools operated fourteen elementary schools, four middle schools, and two high schools. The town also has several private schools and an arts-based charter school. Northwest Arkansas Community College, although located in Bentonville, is supported by tax revenue from and serves Rogers.

During its early years, the economy of Rogers was dependent upon agriculture. Poultry growing and processing became important in the 1930s and remain so today. Major employers now include the Mercy Health System, Tyson Foods of Rogers, Bekaert Corporation, and Glad Manufacturing. In 1962, Sam Walton opened his very first Walmart Inc. store in Rogers, and today many residents work for Walmart Inc. or for one of the many Walmart Inc. vendors with offices in northwest Arkansas.

Recreational attractions include Beaver Lake and the Hobbs State Park–Conservation Area, both east of Rogers. Historical and cultural attractions include the nearby Pea Ridge National Military Park. The Rogers Main Street program has worked to preserve the historic downtown, including the Rogers Historical Museum, the Daisy Airgun Museum, and the Rogers Little Theater; the latter two are included in the Rogers Commercial Historic District, which is on the National Register of Historic Places.

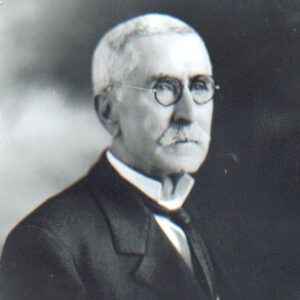

Notable residents include William H. “Coin” Harvey, a well-known political figure who moved to Rogers in 1900. He developed a resort at nearby Monte Ne (Benton County) and, in 1932, ran for president on a third party ticket. Tom Morgan, who moved to Rogers in 1890, was an author of local color stories for such national magazines as the Saturday Evening Post. Betty Blake grew up in Rogers and married Will Rogers in 1908. As Will Rogers became one of the country’s most famous entertainers, Betty helped to guide his career. William Henry Kruse established Kruse Gold Mine but never found any significant amount of gold. Pillstrom tongs inventor Dr. Lawrence G. Pillstrom practiced medicine in Rogers. Gary “Blackie” Bond was one of the most successful high school football coaches in Arkansas history. James William Sutherland Jr., who rose to command the U.S. Army’s XXIV Corps in the Vietnam War, grew up in Rogers. Joe Nichols was born in Rogers and went on to become a star in the county music world.

For additional information:

Collins, Marilyn. Rogers: The Town the Frisco Built. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2002.

“Commemorative Issue: Celebrating Rogers Diamond Jubilee, 1881–1956.” Benton County Pioneer 1 (August 1956).

“Diamond Jubilee Edition.” Rogers Daily News, August 28, 1956.

Muse, Ruth. Rogers to 1929. Unpublished manuscript. Research Library. Rogers Historical Museum, Rogers, Arkansas.

“Rogers Centennial Edition.” Northwest Arkansas Morning News, May 28, 1981.

Rogers Centennial Issue. Benton County Pioneer 26 (Spring 1981).

Vertical files. Research Library. Rogers Historical Museum, Rogers, Arkansas.

Gaye Bland

Rogers Historical Museum

Apple Festival Float

Apple Festival Float  Apple Float

Apple Float  Applegate Drugs

Applegate Drugs  Benton County Map

Benton County Map  Blake House

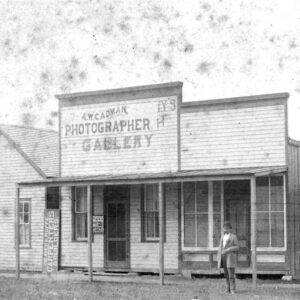

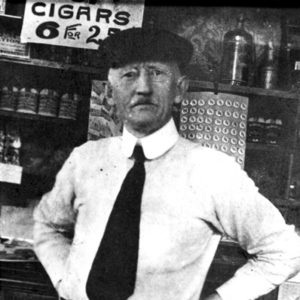

Blake House  Cadman Photographer

Cadman Photographer  Daisy Airgun Museum

Daisy Airgun Museum  Daisy Airgun Museum

Daisy Airgun Museum  Coin Harvey

Coin Harvey  Tom Morgan

Tom Morgan  Rosa Parks Mural

Rosa Parks Mural  Rogers Apple Pickers

Rogers Apple Pickers  Rogers Bridge

Rogers Bridge  Rogers Broiler Show

Rogers Broiler Show  Rogers Businesses

Rogers Businesses  Rogers City Hall

Rogers City Hall  Rogers Firemen

Rogers Firemen  Rogers Historical Museum

Rogers Historical Museum  Rogers Historical Museum

Rogers Historical Museum  Rogers Street Scene

Rogers Street Scene  Rogers Street Scene

Rogers Street Scene  Rogers Street Scene

Rogers Street Scene  Rogers Street Scene

Rogers Street Scene  Rogers Street Scene

Rogers Street Scene  Rogers Street Scene

Rogers Street Scene  Will and Betty Rogers

Will and Betty Rogers  Searles Prairie Natural Area

Searles Prairie Natural Area  Vinegar Factory

Vinegar Factory  First Opening of Wal-Mart

First Opening of Wal-Mart

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.