calsfoundation@cals.org

Jonesboro (Craighead County)

County Seat

| Latitude and Longitude: | 35°50’22”N 090°42’08”W |

| Elevation: | 330 feet |

| Area: | 80.18 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 78,576 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | February 16, 1883 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

155 |

NA |

2,065 |

4,508 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

7,123 |

9,384 |

10,326 |

11,729 |

16,310 |

21,418 |

27,050 |

31,530 |

46,535 |

55,515 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

67,263 |

78,576 |

Jonesboro is the largest community in northeast Arkansas and the fifth largest in the state. It is the Craighead County seat (though Act 61 of 1883 created the “Eastern District of Craighead County,” providing for the establishment of another county courthouse at Lake City due to early difficulties in travel). Jonesboro is a regional center in education, retail, healthcare, and industry; its largest employers are Arkansas State University (ASU) and St. Bernards Medical Center. Jonesboro is also an agricultural center in processing rice, cotton, and soybeans, and it is a regional hub for the food-processing industry, being home to Riceland Foods and plants for Frito-Lay, ConAgra Foods, Kraft Foods/Post Division, and Nestle.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

The Jonesboro area is no a stranger to natural disasters. The New Madrid Earthquakes of 1811 and 1812 created the “sunken lands” in the neighborhood of the city. Crowley’s Ridge, a crescent-shaped rise that is the highest point in northeast Arkansas, was an important factor in Jonesboro’s development because it was safe from the periodic floods that devastated low-lying areas. A Benjamin Crowley built a homestead on the ridge in 1821 to escape the seasonal flooding. A makeshift courthouse was established at Crowley’s settlement, and the area came to be called Crowley’s Ridge.

In 1858, Senator William Jones proposed the creation of a new county. The proposal called for the county to incorporate land from the area represented by Jones’s fellow state senator, Thomas Craighead, who opposed the idea. When the bill passed, Jones proposed that the county be named for Craighead, who, in turn, proposed that the county seat be named for Jones. The town of “Jonesborough” was created, with the spelling later simplified.

Craighead County and Jonesboro were officially born on February 19, 1859. Farmer Fergus Snoddy donated fifteen acres for a town site in the area that is now downtown Jonesboro. Twenty-four years later, with the railroad coming to Jonesboro, voters finally approved the town’s official incorporation in 1883. In 1881, just two years prior, four African-American men were lynched by a masked mob in the vicinity of Jonesboro.

Civil War through the Gilded Age

The town’s population was about seventy-five when Arkansas voted to secede from the Union. On August 2, 1862, the Skirmish at Jonesboro took place on Court Square when Union soldiers captured Confederate troops south of town and took them to the county courthouse. A Confederate unit attacked and drove the Union troops from the town. Jonesboro did not sustain major damage from the war and returned to its agricultural economy afterward.

The town was also the center of a great logging industry at the time, requiring efficient transportation to get the lumber to market. In 1881, the Cotton Belt railroad laid track north of downtown. The Jonesboro, Lake City, and Eastern Railroad connected communities in Craighead County and Mississippi County. Later, the Missouri Pacific, Frisco, and Burlington Northern Santa Fe railroads served Jonesboro. Jonesboro’s growth was significantly enhanced in 1906 with the creation of City Water and Light (CWL) as a municipal utility. CWL continues to serve the town and, due to its extremely reasonable utility rates, is often cited as a major factor in Jonesboro’s growth, attracting business and industry to the area.

Early Twentieth Century

In 1900, following a malaria epidemic, a group of sisters from the Olivetan Benedictine order established a six-room hospital in Jonesboro called “St. Bernard’s” in honor of St. Bernard Tolomei, founder of the Olivetan Benedictines.

In 1904, Woodland College was created, and in 1924, Jonesboro Baptist College was established; both were forced to close within a few years for budgetary reasons. In 1909, the Arkansas legislature passed a law providing for state public schools of agriculture in each of the state’s four districts. Jonesboro competed against Greene County and Mountain Home (Baxter County) to house the school, and after a pledge of $40,000 and 200 acres of land, Jonesboro was chosen. It was named the First District Agricultural School when its first classes were held on October 3, 1910.Now known as Arkansas State University (ASU), it was the first of its sister district colleges to be granted university status.

In 1910, a group of area farmers decided to try growing rice in the fields outside of town. Their success led to the creation in 1930 of what was at the time the largest rice mill in the world, operated by Riceland Foods, Inc. The rice industry continues to be one of Jonesboro’s leading businesses, along with the cotton and soybean industries.

In 1920, African-American man Wade Thomas was lynched after allegedly shooting a white police man.

Jonesboro continued to grow through the 1920s, though its prosperity was muted due to its agricultural economy and the demise of its timber industry when the forests were logged out. As a town with an agriculturally based economy, Jonesboro was forced to weather the Great Depression as best it could. While it was physically safe on the high ground of Crowley’s Ridge from the Flood of 1927, Jonesboro’s economy suffered from the devastating impact on its low-lying neighbors who traditionally came to Jonesboro to shop as well as to process and sell their produce. As the impact from the 1927 flood was beginning to improve, Arkansas was struck by drought in 1930 and 1931, which also had a ripple effect on the town’s economy.

Jonesboro was the center of a small media storm when a supposed ancient artifact dubbed King Crowley was “discovered” in Jonesboro with a number of other similar artifacts during the 1920s and 1930s. These were later discovered to have been manufactured by local resident Dentler Rowland.

In September 1931, the town made headlines in The New York Times for what became known as the Jonesboro Church Wars. Following fiery preaching by the evangelist Joe Jeffers, two opposing Baptist factions fought each other, and gunfire was exchanged before order was restored. Governor Harvey Parnell called out the National Guard and ten state policemen to keep peace. The September 21, 1931, issue of Time magazine called it the Battle of Jonesboro.

In 1920, Jonesboro citizen Thaddeus Caraway was elected to the U.S. Senate. In 1932, his widow, Hattie Caraway, became the nation’s first elected female senator. She often helped Jonesboro by finding jobs on federal projects for poor and handicapped residents, interceded at Arkansas State College to find work-study positions for needy students, and lobbied to build a new post office at Jonesboro.

World War II through the Modern Era

When World War II began, Caraway helped convince the U.S. government to establish a training detachment for the military at Arkansas State College. The College Training Detachment brought GIs from all over the nation to Jonesboro; many settled in town after the war. On September 23, 1944, a county-wide election was held. The vote turned out in favor of creating a “dry” county, outlawing sales of alcoholic beverages.

In 1950, Jonesboro resident Francis Cherry became governor of Arkansas. The town saw a dynamic period of growth in the 1950s and 1960s with the establishment of businesses such as Arkansas Glass, Colson Caster, Frolic Footwear (a division of Wolverine, makers of Hush Puppies), General Electric, Pepsi-Cola, and Hytrol Conveyor Co., one of the largest manufacturers of conveyors and conveying equipment in the world.

Jonesboro’s African-American Cultural Center today emphasizes the history of the black citizens of Craighead County. The E. Boone Watson Community Center in Jonesboro is also dedicated to preserving and remembering black culture in the town, with more than fifty exhibits, including photos, newspaper articles, and other pieces of historic memorabilia. The traditionally black Booker T. Washington High School has held a reunion every two years since 1926 for graduates of Jonesboro’s black school during the segregation period. In 1955, two years before the desegregation of Little Rock Central High School, Army Lieutenant Colonel Frederick Turner Jr., Walter Strong, and Larry Williams began taking classes at Arkansas State College. Strong and Turner were the first two black students to graduate from Arkansas State, in 1959 and 1960 respectively.

On May 31, 1958, the Nettleton community voted 699–76 in favor of a proposed annexation to join the city of Jonesboro. The highly rated Nettleton School District continues to operate independently of Jonesboro schools though it is within the city limits, as do the school districts of Valley View and Westside, which were also absorbed as Jonesboro continued to expand geographically.

The city made national news because of deadly tornadoes in 1968 and 1973, which damaged large parts of the city. The city was also the location of the 1993 March on Religious Freedom, a protest of discrimination against Wiccans and Pagans, which occurred in the light of a renewed “satanic panic” following the the arrest of the West Memphis Three and subsequent 1994 trial in Jonesboro. The school shooting at Westside Middle School on March 24, 1998, resulted in five deaths and again attracted national attention to Jonesboro.

Jonesboro has its own television station, KAIT, an ABC affiliate, plus numerous AM and FM radio stations as well as the Jonesboro Sun newspaper. In addition to the continuous growth of St. Bernards Medical Center, Jonesboro was also served by NEA Medical Center, formerly Regional Medical Center of Northeast Arkansas (established in 1976), before that was replaced by the new NEA Baptist Medical Campus, built on eighty-five acres of land in northern Jonesboro, which opened in January 2014.

The Mall at Turtle Creek, was a $100 million project that was the largest mall in northeastern Arkansas. Nearby towns such as Bono (Craighead County), Brookland (Craighead County), and Paragould (Greene County) have become virtual bedroom communities, as many people come to Jonesboro daily to work. A significant Hispanic population has also been attracted to the town by employment opportunities in construction, agriculture, and food processing. A March 28, 2020, tornado destroyed large parts of the Mall at Turtle Creek and numerous other businesses.

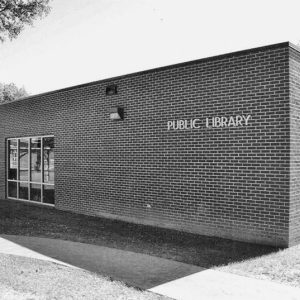

The Jonesboro Regional Chamber of Commerce has been extremely active in recruiting large businesses such as Nestle and Frito-Lay. Local amenities in Jonesboro include the Craighead County Jonesboro Public Library, the Jonesboro Municipal Airport, and the Fowler Center for performing arts.

Jonesboro was home to the magazine African American Perspectives Northeast Arkansas for its publication 2007–2013.

Attractions

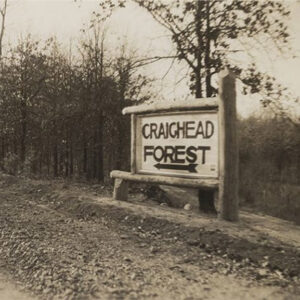

KBTM was one of Arkansas’s early radio stations, first based in Paragould. In just a few years it was moved to Jonesboro. Jonesboro’s Craighead Forest Park is owned by the city and was first developed in 1937, when the local Young Men’s Civic Club began work on the fifty-five-acre lake. Today, the lakeside park offers outdoor sports, hiking trails, camping, fishing (with the lake stocked by the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission), and special events such as July 4th in the Forest and a Labor Day blues festival. In 2004, the Forrest L. Wood Crowley’s Ridge Nature Center opened in Jonesboro, offering visitors a look at the native wildlife of Crowley’s Ridge. The J. V. Bell House, Patteson House, Citizens Bank Building, the Fuller-Shannon House, the Home Ice Company, and the Bridge Street Bridge are all listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Notable Figures

In 1984, local resident Earl Bell won an Olympic medal for the pole vault. In 1990, Debbye Turner, a Jonesboro resident (and daughter of Lieutenant Colonel Frederick Cornelius Turner Jr.), became Miss America. Bestselling author John Grisham, who was born in Jonesboro, chose the town for the world premiere of the television movie based upon his book, A Painted House. Grover Evans, the first black member of the city council, was also a nationally known disability advocate and swimming champion. Other notable residents of Jonesboro have included: politicians Jerry Bookout and John Snyder, environmentalist Julia “Butterfly” Hill, actor Ben Murphy, civic and education leader Edomae Boone Watson, artist Evan Lindquist, New Yorker editor Pat Crow, Arkansas Supreme Court justice Elana Wills, Congressman Rick Crawford, and folk musician Connie Dover.

For additional information:

City of Jonesboro, Arkansas. http://www.jonesboro.org/ (accessed June 28, 2022).

Dew, Lee A. The ASU Story. Jonesboro: Arkansas State University Press, 1968.

Hanley, Ray, and Diane Hanley. Jonesboro and Arkansas’ Historic Northeast Corner. Mount Pleasant, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2002.

McNamee, Heather. “The Road to Respect: African Americans and the Fight for Equal Education in Jonesboro, Arkansas since 1920.” PhD diss., University of Memphis, 2022.

Jonesboro Regional Chamber of Commerce. https://www.jonesborochamber.com/ (accessed June 28, 2022).

Stuck, Charles A. The Story of Craighead County: A Narrative of People and Events in Northeast Arkansas. Jonesboro, AR: 1960.

Williams, Harry Lee. History of Craighead County, Arkansas. Little Rock: Parke-Harper Co., 1930.

Nancy Hendricks

Arkansas State University

Arkansas State University Library

Arkansas State University Library  Arkansas State University Student Union

Arkansas State University Student Union  Arkansas State University Indian Stadium

Arkansas State University Indian Stadium  Earl Bell Community Center

Earl Bell Community Center  Berger-Graham House

Berger-Graham House  Bridge Street

Bridge Street  Francis Cherry and family

Francis Cherry and family  Francis Cherry House

Francis Cherry House  Craighead County Courthouse

Craighead County Courthouse  Craighead County Jonesboro Public Library

Craighead County Jonesboro Public Library  Craighead County Map

Craighead County Map  Craighead Forest

Craighead Forest  Craighead Forest Park

Craighead Forest Park  Crowley's Ridge Nature Center

Crowley's Ridge Nature Center  Gathings Federal Building

Gathings Federal Building  Julia Butterfly Hill

Julia Butterfly Hill  Holy Angels Convent

Holy Angels Convent  Holy Angels Convent

Holy Angels Convent  Jonesboro Main Street, ca. 1900

Jonesboro Main Street, ca. 1900  Jonesboro Islamic Center

Jonesboro Islamic Center  Jonesboro Main Street

Jonesboro Main Street  Jonesboro Soldiers

Jonesboro Soldiers  Jonesboro Street Scene

Jonesboro Street Scene  Jonesboro Street Scene

Jonesboro Street Scene  Jonesboro U.S. Courthouse

Jonesboro U.S. Courthouse  Jonesboro Union Station

Jonesboro Union Station  Joyce's Plaster Palace

Joyce's Plaster Palace  KBTM Tower

KBTM Tower  King Crowley

King Crowley  Malone Theater

Malone Theater  Nettleton Street Scene

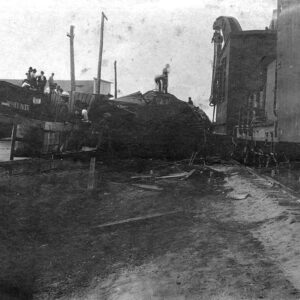

Nettleton Street Scene  Nettleton Train Wreck

Nettleton Train Wreck  Red Cross HQ

Red Cross HQ  Riceland Foods Facility, Jonesboro

Riceland Foods Facility, Jonesboro  Sage Meadows Country Club

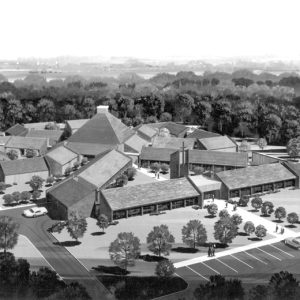

Sage Meadows Country Club  St. Bernards Medical Center

St. Bernards Medical Center  St. Bernards Medical Center

St. Bernards Medical Center  Temple Israel; Jonesboro

Temple Israel; Jonesboro  Water and Light Plant

Water and Light Plant

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.