calsfoundation@cals.org

Butterfield's Overland Mail Company

aka: Overland Mail Company

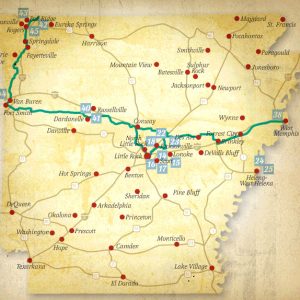

Butterfield’s Overland Mail Company carried the first successful overland transcontinental mail by stagecoach through Arkansas as it went from the Mississippi River to California. Though only running from 1858 through 1861, it was the longest stagecoach line in world history at approximately 2,812 miles and was a major factor in the settlement and development of Arkansas and the American West before the Civil War. Its two main routes ran through Arkansas, westward from Memphis and south from Missouri, connecting in Fort Smith (Sebastian County). Many sites in Arkansas, such as Butterfield Trails Village in Fayetteville (Washington County), still reflect the era of Butterfield’s Overland Mail Company.

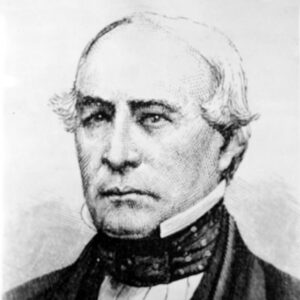

Before modern technology, the mail was America’s lifeblood. “Post roads” were created in the original colonies even before military routes so that the mail could be carried. As the new country expanded west of the Mississippi, Congress recognized the need for an overland mail service to the Pacific. When gold was discovered in California in 1849, bringing over a quarter of a million people to the West Coast, there was a huge demand for transporting mail and passengers. At the time, the usual route was by boat, either around South America or with an overland crossing in Panama, both of which were time-consuming, expensive, and dangerous. After California threatened to secede if a faster mail service was not established, Congress voted in 1857 to subsidize a mail run from the Mississippi River to San Francisco. It required that mail be safely carried in twenty-five days or less. The six-year, $600,000 contract was awarded to John Butterfield, who had an extensive transportation empire based in upstate New York. It was a stock-holding company led by John Butterfield as president, William B. Dinsmore as vice-president, and Alexander Holland (John’s son-in-law) as treasurer.

Butterfield’s contract demanded that service begin within a year. He then had to lay out the route to be followed, needing hard surfaces, gentle grades, and passes that would not be snow-bound in winter. He began the run just west of St. Louis, Missouri, in the town of Tipton, following a southwesterly route through Arkansas, Texas, and Arizona on the journey to California. A connecting route ran from Memphis to Fort Smith, where it joined the Tipton route.

Marquis L. Kenyon (one of the major stock-holders and directors) of Rome, New York, and John Butterfield’s son, John Jr., started in January 1858 by mule back to select the trail through the Southern Overland Corridor, as well as the sites for the stage stations. The stage stations had to be stocked with horses, mules, harnesses, food, supplies, wagons, and other equipment. Some 1,500 employees were hired as station masters, superintendents, line riders to keep the trail in shape, vaqueros (Mexican cowboys) to take care of the stock, stage conductors, and stage drivers. About 1,000 livestock were needed, and thirty-six Concord stagecoaches were used on the settled sections of the trail, while sixty-six Concord stage (celerity) wagons were used on the 1,920-mile frontier section between Fort Smith and Los Angeles, California. There were fourteen stages in operation at any given time, and the rest of the stages were stored at regular intervals at the stations. Most of the stage drivers and superintendents were from upstate New York.

On September 16, 1858, the first stagecoach of Butterfield’s Overland Mail Company originated in Tipton, and on September 18, it made its first stop in Arkansas. On this inaugural trip, John Butterfield himself rode the stage to Fort Smith. Its first Arkansas stop was at a spring near what is today Rogers (Benton County) and was called Callahan’s Tavern. It then went south to Fayetteville. This was a major stop, since the route from Fayetteville through the rugged Boston Mountains to Fort Smith required that the horses be exchanged for mules, animals that could better make the arduous trip.

Butterfield seemed impressed by the town of Fayetteville. Before the Civil War, it boasted educational institutions such as the Fayetteville Female Seminary and Arkansas College. He may have recognized it as an important destination for students, educators, and their families, for he recruited his own son Charles to be stationed in Fayetteville and bought property there, where he entertained friends and business associates.

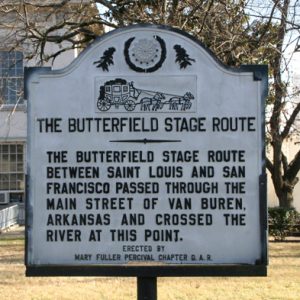

The first Butterfield stage entered Forth Smith on Sunday, September 19, 1858, at 2:00 a.m. Its route took it over Fort Smith’s old Washington Street, which today is 2nd Street. Even at that hour, its arrival was greeted with music, cheering, and cannon fire, which continued until the coach left for California.

Butterfield’s advice to his drivers was: “Remember, boys, nothing on God’s earth must stop the mail!” When the Butterfield stage came to isolated towns, it was cause for celebration. Butterfield coaches were their connection to the rest of the country. Mail and passengers were transported to remote places in the vast American West.

A well-preserved Arkansas way station for Butterfield’s Overland Mail Company, the home of John Kirkbride Potts, is still standing in Pottsville (Pope County) and is maintained as the Potts Inn Museum on Highway 247 by the Pope County Historical Foundation. Other Arkansas stops between Memphis and Fort Smith included Madison (St. Francis County); Des Arc (Prairie County); Atlanta—now Old Austin (Lonoke County); Cadron (Faulkner County); Plumer’s Station—now Plumerville (Conway County); Hurricane (Pope County); Norristown (Pope County); Dardanelle (Yell County); Stinnett’s Station (Logan County); Paris (Logan County); and Charleston (Franklin County). The northwestern route that came out of Missouri included stops at Callahan’s Station—now near Rogers; Fitzgerald’s Station—now Springdale (Washington and Benton counties); Fayetteville; Park’s Station—now Hogeye (Washington County); Brodie’s Station—now Lee Creek (Crawford County); Woolsey’s Station, also called Signal Hill (Crawford County) (this was likely Woosley’s station instead, located between the stations at Lee Creek and Fort Smith, and later recorded incorrectly as Woolsey’s); and Van Buren (Crawford County), where, beginning in 1860, the stage crossed the Arkansas River on its way to Fort Smith.

In March 1860, John Butterfield was voted out of office by the stockholders as he was not making money for them and had defaulted on a $162,000 loan. He remained as a director and attended the meetings at the company’s office in New York City. Vice President William B. Dinsmore became president and remained in that position until the end of the contract on September 15, 1864.

Because of the impending Civil War, the line was ordered by Congress on March 2, 1861, to transfer all equipment, livestock, and personnel to the Union-held Central Overland Trail, where the six-year contract was completed September 1864. The Confederate army had confiscated Butterfield’s stages in Texas to convert them to military vehicles, but eighteen of his stage wagons managed to make it to the Central Overland Trail.

The company’s colorful past can still be found in towns with streets called Stagecoach Road, a tribute to the courage and tenacity of those who rode Butterfield coaches into history. Four segments of the roads that Butterfield’s Overland Mail Company traveled over in Arkansas have been listed on the National Register of Historic Places. They are the Fayetteville Segments Historic District in Lake Fayetteville Park in Fayetteville, the Lucian Wood Road Segment on Lucian Wood Road between the junction of Armer Lane and Cedarville Road and Arkansas Highway 220 near Cedarville (Crawford County), the Lee Creek Road Segment on Lee Creek Road west of Arkansas Highway 220 near Cedarville, and the Strickler Segment that follows Bugscuffle Road south of Strickler (Washington County) and Old Cove City Road north of Chester (Crawford County). Each of the segments was recognized on the National Register as “a tangible reminder of the stagecoach line that provided the first transcontinental mail service in the United States. The road provides a unique opportunity to share the experiences of the nineteenth-century travelers who braved the rough roads from Missouri to California.”

In January 2022, U.S. Senator John Boozman filed a bill to have the Butterfield Overland Trail designated a national historic trail, after filing a similar bill in 2020, only to see if die in committee. At the end of 2022, the trail was designated a national historic trail, including two portions that cross Arkansas.

For additional information:

Ahnert, Gerald T. The Butterfield Trail and Overland Mail Company in Arizona, 1858–1861. Canastota, NY: Canastota Pub. Co., 2011.

———.“Identifying Butterfield’s Overland Mail Company Stages on the Southern Trail, 1858–1861.” Overland Journal: The Official Journal of the Oregon-California Trails Association 32 (Winter 2014–2015): 140–164.

Bowden, Bill. “Senator Pushes Bill for Butterfield Trail.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, January 31, 2022, pp. 1B, 3B. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2022/jan/31/us-sen-boozman-wants-national-designation-for/ (accessed July 28, 2023).

“Butterfield Overland Mail Route, Fayetteville Segments Historic District.” National Register of Historic Places registration form. On file at Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, Little Rock, Arkansas.

“Butterfield Overland Mail Route, Lee Creek Road Segment.” National Register of Historic Places registration form. On file at Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, Little Rock, Arkansas.

“Butterfield Overland Mail Route, Lucian Wood Road Segment.” National Register of Historic Places registration form. On file at Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, Little Rock, Arkansas.

“Butterfield Overland Mail Route Segment.” National Register of Historic Places registration form. On file at Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Crossman, Bob. “The Butterfield Overland Mail Company: Faulkner County Connection.” Faulkner Facts and Fiddlings 63 (Fall 2021): 24–32.

———. Butterfield’s Overland Mail Co. Stagecoach Trail across Arkansas, 1858–1861. N.p.: 2021.

———. Butterfield’s Overland Mail Co. Use of Steamboats to Deliver Mail and Passengers across Arkansas, 1858–1861. N.p.: 2022.

———. “Fort Smith’s Connection to Butterfield’s Overland Mail Co.: Stations between Memphis and Fort Smith.” Journal of the Fort Smith Historical Society 45 (September 2021): 25–44.

Conkling, Roscoe P., and Margaret B. Conkling. The Butterfield Overland Mail, 1857–1869. Glendale, CA: A. H. Clarke Company, 1947.

Greene, A. C. 900 Miles on the Butterfield Trail. Denton: University of North Texas Press, 1994.

Ormsby, Waterman L. The Butterfield Overland Mail. San Marino, CA: Huntington Library Press, 1988.

Root, Frank A., and Elsey Connelley. The Overland Stage to California. Topeka, KS: 1901.

Rose, F. P. “Butterfield Overland Mail Company.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 15 (Spring 1956): 62–75.

Sanders, Kirby. “Gladden, Woolsey, Woolum, Woosley, and Zion: Facts and Folklore of the 19th Century Stagecoach Routes in Washington County.” Flashback 59 (Fall 2009): 101–114. Reprinted in Benton County Pioneer 54, no. 2 (2009): 6–11. Online at http://frontierhistory1.blogspot.com/2011/07/gladden-woolsey-woolum-woosley-and-zion.html (accessed December 4, 2023).

Wood, Ron. “Butterfield Trail Receives National Designation.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, December 23, 2022, pp. 1B, 3B. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2022/dec/23/butterfield-trail-gets-national-historic/ (accessed July 28, 2023).

Nancy Hendricks

Arkansas State University

Gerald T. Ahnert

Syracuse, New York

Arkansas Heritage Trails System

Arkansas Heritage Trails System Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood, 1803 through 1860

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood, 1803 through 1860 Southwest Trail

Southwest Trail Transportation

Transportation Butterfield Trail

Butterfield Trail  John Butterfield

John Butterfield  Butterfield's Overland Comapny

Butterfield's Overland Comapny  Butterfield's Plaque

Butterfield's Plaque  Greathouse Home

Greathouse Home  Potts Family Marker

Potts Family Marker  Potts Inn

Potts Inn  Potts Inn

Potts Inn  Potts Inn Museum

Potts Inn Museum

There was never a Butterfield stop at Woolum/Woolsey/Signal Hill. I’ll cite a 2009 article by Kirby Sanders “Thereafter, folklore and anecdote have maintained that the Butterfield coaches stopped in the vicinity of Signal Hill west of Winslow. This station at Winslow is frequently referred to as the “Woolsey” or “Woolum” Station and is often claimed as what contemporaneous reports call the “Woosley Station.” This Winslow-area station is most assuredly a later coach stop unrelated to the Butterfield. For starters, a sidetrack from Strickler to Winslow would have required a due-east side track of almost seven straight-line miles–and given the terrain of the area, there is no such thing as “straight-line miles.” This region is among the most rugged of the Boston Mountain area and would have required an arduous (if not impossible) passage for horse-drawn coaches. On existing roads this sidetrack is a 22 mile trip. The most-direct route through the same terrain would have required at least seven hours for the Butterfield coaches. To reach the next confirmed stop at Brodie’s Station near Lee Creek would be another 26 treacherous miles requiring another eight or nine hours to complete.” Instead, it should be a stop a WOOSLEY station. Sanders: “By contemporaneous reports from both Waterman Ormsby and Bailey, Woosley’s Station was located between the stations at Lee Creek and Fort Smith — both of which are well south of Signal Hill / Winslow. Ormsby’s and Bailey’s 1858 reports have also been confirmed by Lemke (1958 but incorrectly noted as “Oosley’s Station”), Conklings (1947), Mincke (2005), and the Matt brothers (2006). The identified site of this station is in Crawford County in the vicinity of the intersection at Arkansas 220 / Uniontown Highway and Arkansas 59 south of Cedarville.” https://frontierhistory1.blogspot.com/2011/07/gladden-woolsey-woolum-woosley-and-zion.html